Under the title Collective Mending, the seventh edition of the Sustainable Challenge, led by MODA-FAD, invites us to pause, observe, and mend, imagining a future where repair becomes the core of creativity and sustainability rather than a nostalgic gesture. From November 12 to 15 at Disseny Hub Barcelona, the challenge kicks off with a public talk by curator Amy Twigger Holroyd on repair as a collective act, inviting attendees to bring a garment to be transformed by international student teams and showcased in the final runway show.

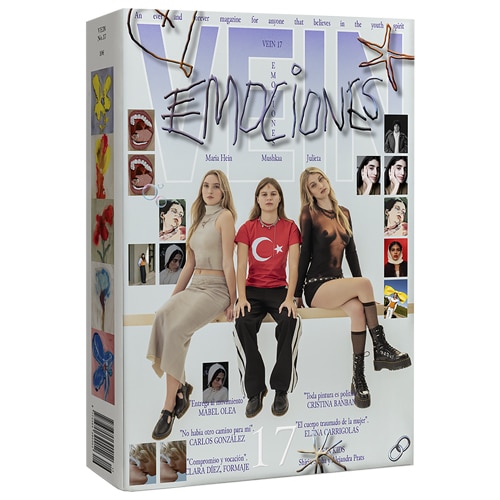

Urtikarie project by Martina Mefano

At the heart of Sustainable Challenge 2025: Collective Mending, curators Amy Twigger Holroyd, Martina Mefano, Mats Siffels and Penny Papachristodoulou propose a dialogue between design and repair, a process that celebrates imperfection as transformation. Organized by MODA-FAD, with the support of the Ajuntament de Barcelona and Disseny Hub Barcelona, the backing of the Generalitat de Catalunya, and in collaboration with the Embassy of the Netherlands and the British Council, the project gathers students from European design schools for a collective creation marathon exploring the idea of dynamic repair, an approach that transforms garments into something new, celebrating their imperfections as traces of life and evolution. Far from the logic of fast consumption, this exercise proposes a paradigm shift, placing existing garments and their wearers at the center of the creative process. To learn more about this philosophy and the role design plays in imagining more sustainable futures, #VEINDIGITAL spoke with Amy Twigger Holroyd, professor of alternative fashion systems at the Nottingham School of Art & Design and curator of the project.

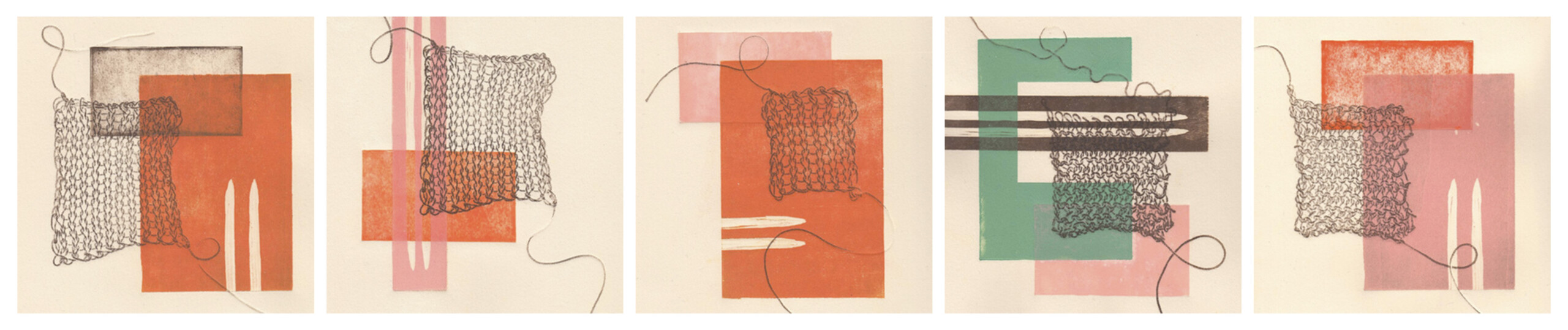

Needles and yarn by Amy Twigger Holroyd

What makes the act of mending a political gesture and a form of resistance in an industry that encourages replacement over repair?

The mainstream fashion industry is driven by the production of ever-increasing volumes of clothes, and this overproduction drives a culture of overconsumption – buying more and more, without a thought for the option to repair. In this context, doing anything to extend the life of the things you already have is a form of resistance. It’s a quiet kind of activism that shows another way of ‘doing fashion’ is possible. Even sustainable fashion is often framed around shopping – buying one item rather than another. But we’re never going to shop our way to sustainability: the most sustainable garment is the one you already own. Taking care of the items in your wardrobe is therefore a really important – and very accessible – act.

The title of this edition, Collective Mending, suggests that repairing is not just an individual act but a communal practice. What changes when mending becomes a collective activity?

Historically, mending has long been a communal activity. People in many cultures have traditionally gathered together in the evening to mend and tell stories. Today people are again getting together to mend, whether at organised Repair Cafes and darning workshops or informal social groups. When people mend together, they have the opportunity to share skills and experiences, motivate one another to mend, and – importantly – to collectively validate mending as a socially valuable activity. In a culture where mending is marginal, this social support is crucial for mended clothes to be widely accepted and even desired.

What inspired the decision to focus the 2025 edition on collective mending, and how do you think this theme reflects the current challenges of sustainable fashion?

The Challenge organisers identified the theme of mending and approached me to take on the role of guest curator, because my academic research and practice has explored remaking and repair in the fashion context. I think it’s a great theme that draws out some fascinating sustainable fashion issues. By focusing on mending, we’re addressing overproduction and overconsumption; by thinking about design for mending, we’re looking at how design could be used differently; by working collectively, we’re challenging a culture of individualism and competition.

Urtikarie project by Martina Mefano

Mending implies embracing imperfection, even celebrating it. How can design learn from mistakes, visible repairs, and elements that are intentionally imperfect?

Lying underneath the mainstream culture of fashion design is an ideal of the blank slate and endless possibility: designers are trained to be true to their unique vision and to find whatever is needed to bring that vision to life. Mending challenges all of this: not only does it embrace imperfection, but it also requires the designer to work within the specifics of the existing garment and the needs and preferences of the wearer. At times, the aesthetics of imperfection are celebrated within the commercial fashion system: patched garments have appeared in the catwalk shows of mainstream brands. But this is a hollow imitation of mending, rather than a meaningful engagement: there are much more radical lessons that could be learned. What would happen, for example, if brands were to really take responsibility for the multitudes of garments that they have already produced?

In ‘Folk Fashion: Understanding Homemade Clothes’ you explore how creating or altering garments generates attachment and memory. How can this emotional connection transform the way we design, and could emotional durability be as valuable as aesthetics or functionality?

Making and mending can generate attachment – although I should highlight that this doesn’t automatically lead to positive memories! I often encounter a romantic view of making that doesn’t entirely chime with the lived experiences of makers, which sometimes involve disappointment. But certainly, the idea of emotional durability is very interesting to explore in design. About twenty years ago I founded a slow fashion knitwear label, Keep & Share, and tried to design long-lasting clothes by supporting emotional connection between wearer and garment. I think I had some success with this, but research by sustainable fashion pioneer Kate Fletcher has shown that wearing practices are far more idiosyncratic than they might appear: there’s a limit to the designer’s influence, especially once the garments are out of our hands. It might, however, be productive to think about how a designer could support emotional connection through repair, using design-led material intervention to help to reconnect a wearer with their garment, and this is an idea that we’ll be exploring in the challenge.

In your research on regenerative design, you discuss fashion capable of restoring relationships—with people, materials, and the environment; what challenges do you face when trying to regenerate instead of produce?

I think the central challenge is the dominance of the mainstream system: it not only accounts for the vast majority of clothing production and consumption, but actually colonizes our ideas about what is possible in fashion. The idea that the fashion system will be driven by growth and the pursuit of profit, and that it will revolve around the production of more and more clothes, is so entrenched that ideas about alternative fashion systems can seem very far-fetched. We assume that fashion design means the production of new garments and collections, but there are so many other ways to design for fashion that would support regeneration: designing services, systems, even alternative economies.

This challenge involves young designers from different countries; what would you like them to take away from this experience beyond a collection or a project?

I’m hoping that they’ll take away insights into others’ cultural experiences and ways of working. When I was younger I did a cross-institutional Masters course, which involved studying in the Netherlands and France as well as in the UK, and I found it fascinating to learn alongside others with different perspectives on fashion design and on wider aspects of society and culture. I still think back to those experiences now – so I hope that this intensive challenge, which brings together students from eight countries, will be just as memorable for them.

Urtikarie project by Martina Mefano

How are participants selected and guided during the challenge to ensure they balance creativity, sustainable thinking, and practical problem-solving?

We had an amazing response to the call for participants, and it was a really difficult job to make the selection. I looked out for applicants who demonstrated an open mind and an experimental approach to design for mending. During the challenge, we’ll be guided by a vision of a fictional world in which mending is a central, celebrated part of fashion culture. This playful approach is linked to my Fashion Fictions project, which brings people together to imagine, explore and enact engaging fictional visions of sustainable fashion systems. The groups will be invited to develop their own ‘mending salons’, each with their own aesthetic specialism, and to start the design process from real garments in need of mending, put forward by real wearers.

During the challenge, participants work with existing materials and collaborate in teams; what methodologies or dynamics do you encourage to help them experiment with new ways of mending, reinterpreting materials, and learning from each other?

We’ll be providing expert masterclasses to inform the students’ developing ideas, spanning both hands-on mending techniques of darning, patching and overprinting and activities to support the envisioning of the mending-focused world. Some activities will involve all of the students, some just representatives of each group. At times we’ll bring members of different groups together, reflecting the idea that in the parallel world, the mending salons work cooperatively, rather than competitively.

Collective Mending also addresses social and cultural narratives embedded in textiles; how important is storytelling in the projects that emerge during the challenge?

Textiles are full of narratives and mending adds more layers of narrative; every mended garment tells a story. I was excited to see that some of the students who applied for the challenge highlighted the cultural meanings of textiles and of mending, and I’m looking forward to hearing the stories of their personal experiences and supporting them to incorporate these insights into their design ideas. We’ll also be telling a story together, bringing to life the world of mending salons and making it feel real, for just a few days.

Looking ahead, how do you envision the impact of Sustainable Challenge extending beyond the event, both for the participants and for the fashion industry as a whole, and is there any concrete lesson from this edition that could inspire brands or designers?

I’m hoping that the challenge will provide an engaging example of playing with the fashion system, using practical enactment as a way of exploring an alternative possibility and, along the way, highlighting aspects of the dominant system that easily pass unnoticed. I would love to see some of the ideas that the students generate together bleeding into the real world, perhaps through new aesthetics for mending or through new ways of designers organising together to provide innovative and enticing repair services.

Urtikarie project by Martina Mefano

–

More about the Sustainable Challenge 2025 at FAD.cat