Anna Voda turns the everyday into a spell—washing machines, blenders, sunlight, and lost brushes become portals into worlds where domestic quiet becomes cinematic magic, and femininity rewrites its own gaze.

Anna Voda paints like someone who’s learned to treat the world as raw material, every hum, gesture, and sunbeam becomes a signal, a doorway, a provocation. Her work turns the domestic into the cinematic: washing machines become portals, irons become chess partners, a water bottle becomes a tiny shrine to light and touch.

Moving from Kharkiv to Lisbon, from theatre sets to jewellery studios, she’s built a practice where scale is psychological, colour is emotional architecture, and women are seen through a woman’s own gaze, tender, daring, and unbothered by cliché. We speak about accidental muses, lost brushes, the secret lives of colour, and the strange magic of everyday objects.

Andriy Zozulya: You describe turning a blender’s hum, a hand gesture, or sunlight on blinds into a painting. What’s the quirkiest everyday sound or scene that got you thinking: “That’s a painting right there”?

Anna Voda: I see paintings all around me. The key is to look closely, to notice what catches your attention, what “rings.” For example: The sound of a washing machine for me is like a portal into a new world, a world of cleanliness and things ready for a new use.

The drum spins, the water bubbles, the door creaks open, and immediately an image appears: objects whirling in rhythm, me spinning along with them, falling into a moment of change where the air almost tangibly smells of freshness. And voilà. we’re on a picnic!

This sound becomes an impulse for a painting: I catch it, observe the details, and transform a mundane domestic moment into a tiny mythical world. The sound of completed laundry.

When you started your journey from Kharkiv to Lisbon, how many brushes got lost in transit, and did any of those losses turn into inspiration instead of frustration?

On my journey trough the countries where i lived to Lisbon, I lost six brushes. three cheap ones, two favorites, and one that I still miss a little. But honestly, each loss became a kind of permission: to change a line, relax my hand, let a gesture breathe differently.

When you move between cities, you realize the only studio you truly carry with you is your own body. Everything else can be replaced, and sometimes those replacements bring a new rhythm, new colors, and brushes that let you expand the world even more beautifully.

Your palette jumps from deep, ritual-ish reds to bubble-gum pinks and electric blues. If you had to pick one colour as your secret weapon, what would it be and why?

If I had to choose one color as my secret weapon, it would be wine red. But I can’t resist another, sky blue, its quiet, dear brother, the head of all beginnings.

Wine red remains the heart of my palette: both bodily and symbolic, pulse, a bruise, a burgundy drape in a vintage hotel, a lover’s lips, memory. A color that holds intimacy and a subtle danger, one that allows me to show everyday life as something tender but a little daring.

Sky blue, on the other hand, is the opposite, breath, space. It gives room, silence, vertical light. It’s the color of morning air, sheets on the wind, the pause between gestures.

Together they work like impulse and breath, like body and the space around it.

This is my little duet.

You’ve worked across jewellery studios, theatre decor, interior design, then returned to painting. What studio detour taught you the most surprising lesson you still use today?

The irony is that I’m naturally terribly fidgety, I need movement, a change of rhythm, a change of tasks, and probably that’s why theater and event set design welcomed me so easily: they live at the same pace as I do.

The most unexpected lesson came from working in theatre workshops. That’s where I first realised that scale is psychological, not physical. A two-meter set can feel weightless, almost fragile, while a tiny object can dominate a space like a massive monolith.

Yet it was in jewellery workshops, where I worked for five years, that I learned to sit, breathe, focus, hold my hand as if the whole world depended on a single millimetre. This was my personal lesson in patience and attention. Even my smallest paintings now remain spaces that a viewer can step into — like a room, like a stage, like a moment.

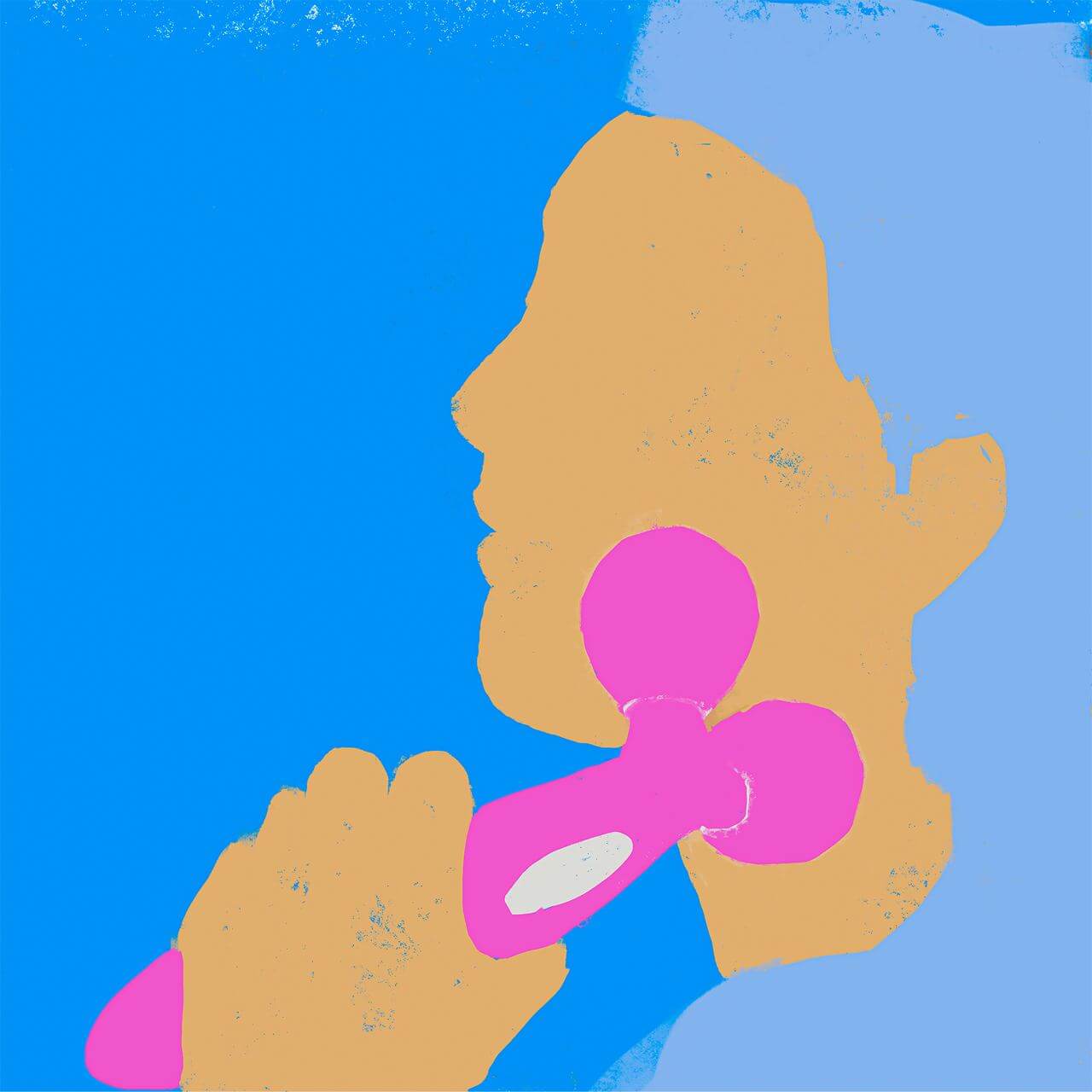

In your “Woman” series you paint women the way a woman looks at another woman, tender, curious, free of clichés. What’s one cliché you still secretly enjoy breaking in your work?

In the “Woman” series, I continue to break one of the most persistent clichés, that a female body must be “proper” and safe, and cannot be shown as an object of desire if you are a woman. The truth is, I love “objectness” in everything: sex, work, art. I like that delicate balance where cynicism meets sensuality, where the body can be at once form, figure, symbol, and pleasure.

For me, “objectness” isn’t about humiliation, it’s about clarity. It’s about a woman choosing when to be the image, when to be the power, when to be the gaze and when to be the object of that gaze — including her own.

I enjoy playing with this tension: how the female figure can be exposed but not submissive;

desirable but not intended; vulnerable but absolutely independent. There’s honesty, freedom, and a little cheeky pleasure in this, and that’s what I bring to my work.

If your painting practice had its own soundtrack (and you’ve said each piece has a playlist), what three songs would open your current series?

Three tracks that would open the soundtrack for my current series, Body Poetry: “Blues Force” by Fourplay, “Is It a Crime” by Sade, and “Santorini” by Donny Benét. They set the right flow: sensual, cinematic, a little morning-y, when the light is still soft, gestures are slowed, and the body remembers all its desires. The music moves the brush confidently, lazily, sexily relaxed, this is exactly how the series begins.

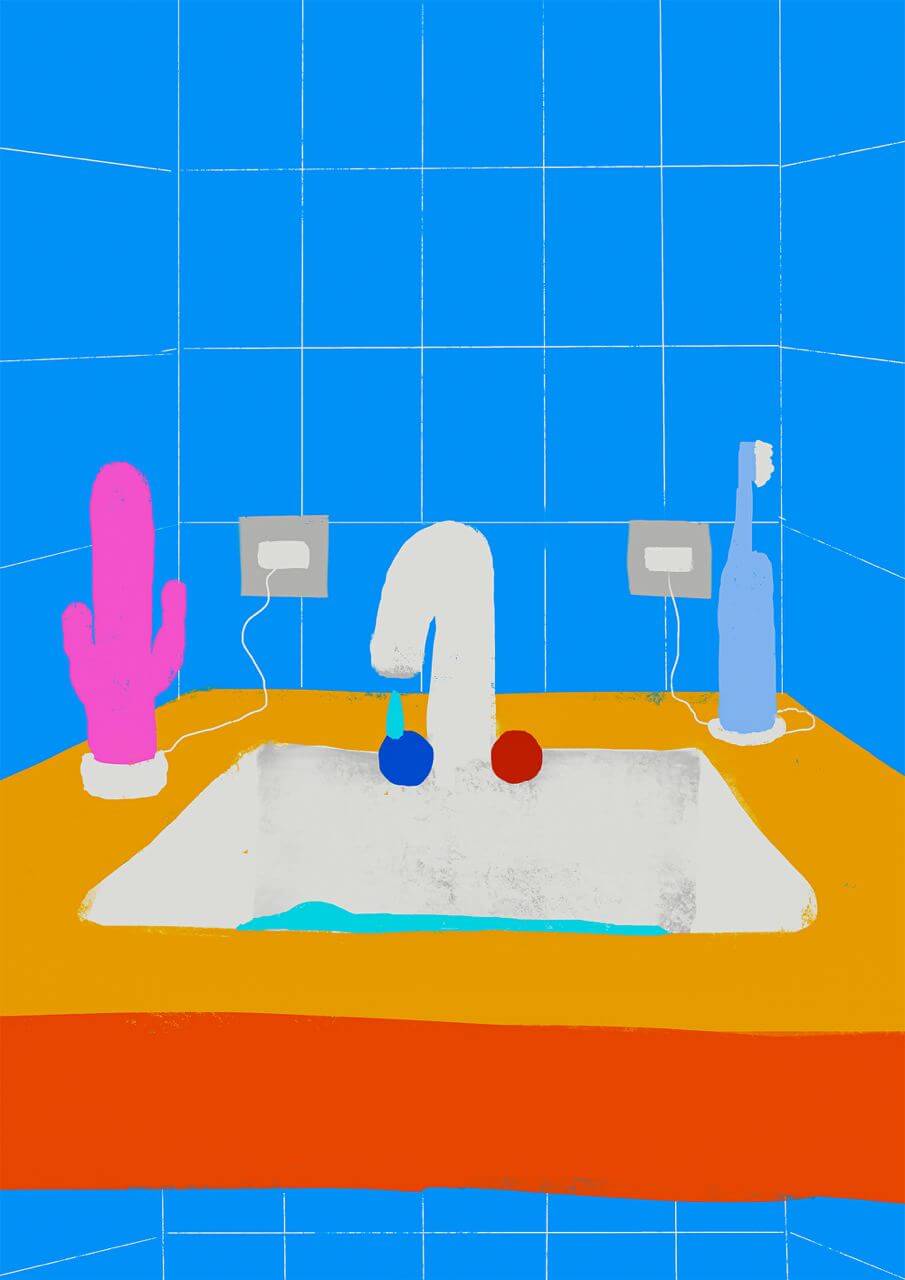

You turned the mundane into myth, as you say, ironing, cooking, skincare tools all become icons. Which household object next is on your radar for myth-making?

The next household object I want to mythologize is a water bottle. At first glance, it’s simple, transparent, everyday. But in my eyes, it becomes almost a ritual object: it reflects light, slides through the hand, droplets playing on the skin like tiny suns.

Drinking from it is a small act of self-care, almost a meditation, an intimate moment within everyday chaos. I want to show how something so ordinary can gain magic: a drop of water becomes movement, the bottle becomes sculpture, and a simple sip becomes an entire ritual.

If you could step into one of your own paintings for 24 hours (with all its colour, symbolism and light), which one would it be and what would you do inside it?

If I could step into one of my paintings for 24 hours, I would choose the one that started this whole series, made during Covid, when out of boredom and tenderness toward the world and myself, I played chess with an iron.

Inside this painting is that strange freedom I lived then: when time flowed differently, when the home became a universe, and every object became a partner in play, dialogue, and silence. I would sit on the floor again, feel the warm surface of the parquet, listen to how the light breathes in the room.

I would stroke the iron like a funny character and make a few absurd but utterly honest moves. Probably, I would just let myself be — no schedules, no cities, no expectations, no war.

To exist in a space where the mundane turns into myth, and loneliness becomes a game. This state still lives in my work today: slightly strange, slightly domestic, fairy-tale everyday — and wonderfully warm in its own way.

Images courtesy by Anna Voda