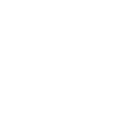

Adolescence is a threshold. No longer a child, not yet an adult, the teenager inhabits a liminal space of emotional intensity and uncertainty. This in-between defines girlhood as a cultural condition, traced through the narratives of cinema, photography, and fashion. In #VEINDIGITAL we spoke with curator Elisa De Wyngaert about how these visions converge in GIRLS, the new exhibition at MoMu.

Sisters (1976), Jim Britt. Used in the Comme des Garçons Fall/Winter 1988–89 campaign.

Girlhood is a space of contradictions: a phase both invisible and hyper-exposed, fragile yet defiant. ‘GIRLS. On Boredom, Rebellion and Being In-Between’ at MoMu (27 September 2025 – 16 February 2026) situates these tensions within a broad historical and cultural framework. Echoed in the catalogue, this perspective draws on thinkers such as Mary Wollstonecraft, Simone de Beauvoir and Judith Butler to show how the adolescent girl has long been framed as a contested cultural battleground, charged with expectations, anxieties, and projections.

Alongside these theoretical frameworks, GIRLS grounded its narrative in the present by engaging female voices across generations through focus groups. “The insights from these sessions formed the foundation and confirmed some key themes in the exhibition, such as exploring the inner worlds of teens through sleep, boredom, and rebellion, and served as a starting point for the video installation by director Leonardo Van Dijl, in which he interviews ‘girls’ between the ages of 9 and 80,” explains curator Elisa De Wyngaert.

Adolescence today unfolds against a backdrop of mounting pressures: long waiting lists for mental health support, persistent poverty, and the constant negotiation of online identities. “Society and governments should do more to understand and research the issues teenagers face today and address their basic needs. In Belgium, for instance, there are long waiting lists for psychologists and psychiatrists, and many children live in poverty. Teenagers do face immense pressure – some of it specific to today, like navigating online identities, but much of it tied to universal coming-of-age emotions that resonate across generations”, says De Wyngaert.

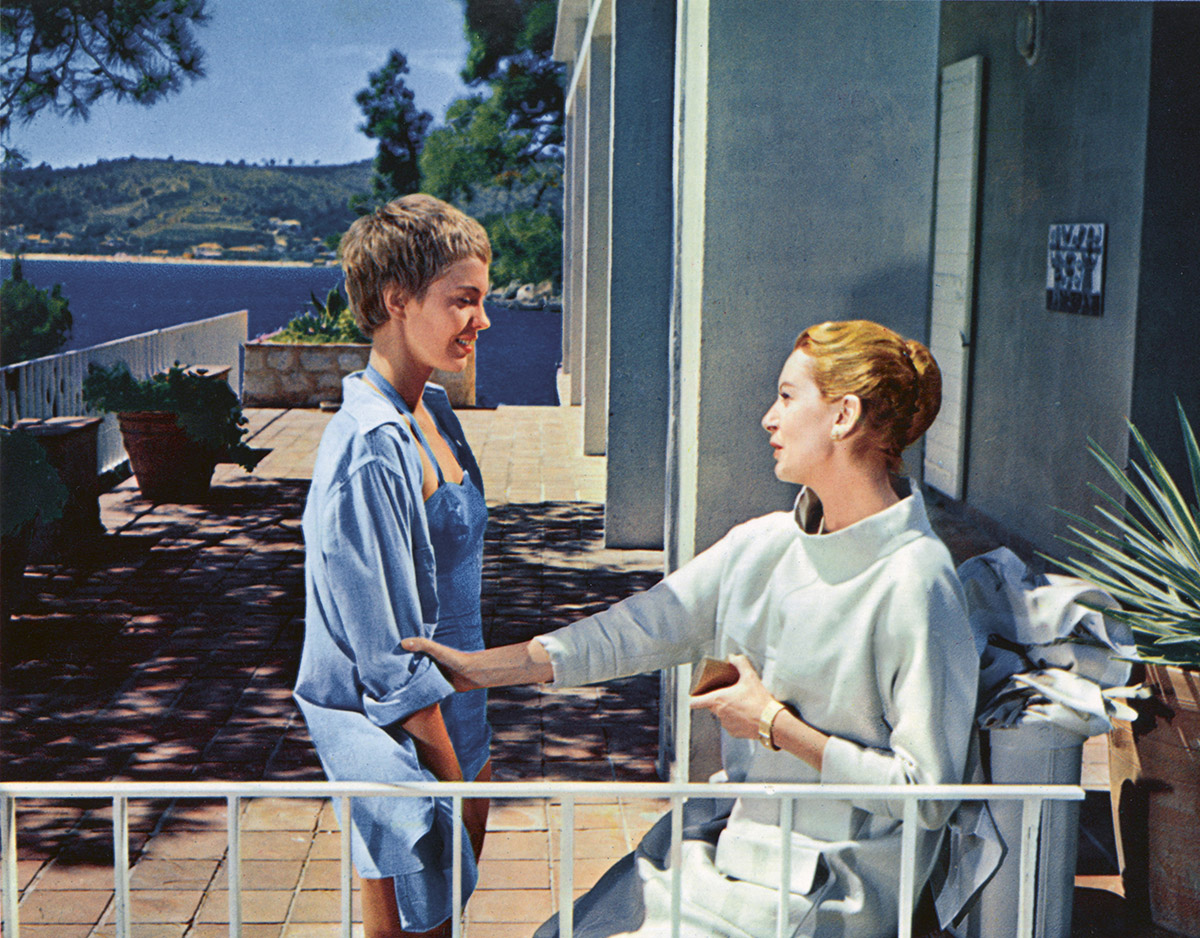

Micaiah Carter, Adeline in Barrettes, 2018

Amid these challenges, help shift the focus toward connection, imagination, and resistance. As the curator points out, “art and culture can play an important role: they foster intergenerational understanding, show young people that the intensity of this phase is normal and temporary, and create a sense of camaraderie. And beyond reflecting anxieties, art and fashion can capture the fun, beauty, and creativity of girlhood and teendom, making it also about bonding, finding your voice, and carving out a place in the world through creative expression”

One of the exhibition’s defining principles is inclusivity, ensuring that girlhood is not framed solely through a Western lens. “For many women artists, memories and emotions from adolescence have always been central to their work. I wanted to bring together artists, filmmakers and designers who deeply resonate with this sentiment, showing how girlhood emerges as a delicate, subversive, and unresolved language across fields. Much of the work in the exhibition articulates the idea that girlhood isn’t something we leave behind, but a way of seeing that stays with us — and that perspective knows no European borders.” Among the artists presented are Frida Orupabo, born of Norwegian and Nigerian heritage, whose collages confront the racialized construction of femininity; Arisa Yoshioka, whose photographs explore identity from Mongolia; and Fumiko Imano, whose staged self-portraits from Japan interrogate performance and multiplicity.

Fumiko Imano, Yellow bath/Hitachi/Japan, 2007

A key dimension of GIRLS is the way it integrates trans and non-binary perspectives into its narrative, challenging the rigid gender codes that have historically confined girlhood. “In the early 20th century, children’s fashion became increasingly gendered: young boys traded dresses for shorts or trousers by the age of six, while girls’ clothing remained decorative and restrictive, anticipating their future roles as wives and mothers. These binaries of dress have proved remarkably enduring. Yet, as Judith Butler argued in Gender Trouble (1990), gender expression is not fixed at birth but continually shaped by culture, upbringing, and experience. Trans and non-binary perspectives expand this understanding of girlhood by challenging the rigid codes of dress and behavior that once confined it, showing instead that girlhood can be imagined as a fluid, evolving space of identity rather than a predetermined role.”

Nigel Shafran, Teenage Precinct Shoppers, 1990

Nigel Shafran, Teenage Precinct Shoppers, 1990

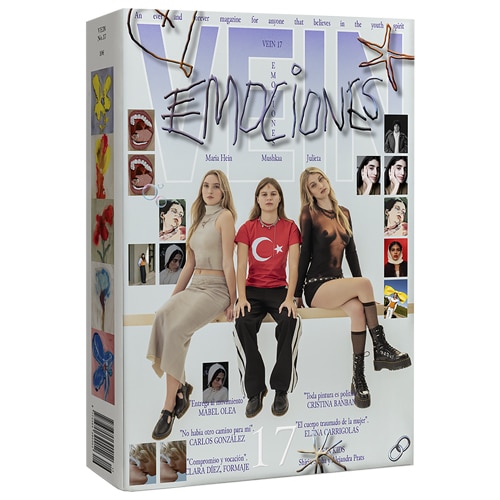

From The Wizard of Oz (1939) to The Little Girl Who Sold the Sun (1999), through The Virgin Suicides (1999, Sofia Coppola) and Girlhood (2014, Céline Sciamma), up to the 2025 adaptation of Bonjour Tristesse by Durga Chew-Bose, cinema has long shaped the visual language of adolescence, a constellation of images that also defines the universe of GIRLS. “We included a montage of girls’ fashion on film, showing how clothing can disrupt cinema’s patriarchal gaze. Across these clips, a sense of rebellion builds: from girls being dressed by others to claiming their own identity, from uniformity toward freedom. Highlighting fashion in coming-of-age films also gives overdue credit to the costume, hair, and make-up artists whose work shapes the iconic images through which we recognize our shared girlhoods. The film installation in the show was curated by Claire Marie Healey.”

Jean Seberg and Deborah Kerr in Bonjour Tristesse, directed by Otto Preminger based on the novel by Françoise Sagan, 1958

Christiane F – Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo, directed by Uli Edel based on the autobiography by Christiane Felscherinow, 1981

Still from The Virgin Suicides, 1999, directed by Sofia Coppola

Photography in GIRLS also traces how the image of teenage girls has been staged, mythologized, and reimagined across decades. From Tina Barney’s The Dollhouse (1986) and Nancy Honey’s Entering the Masquerade (1992) to Harley Weir’s i love you as a friend (2025), the exhibition shows the shifting ways girlhood has been represented. “Images of teenage girls have long been constructed and consumed through books and magazines, often reinforcing stereotypes. We show different sides of girls in print and photography in the exhibition. Today, the important work of photographers like Lauren Greenfield, Leticia Valverdes, Eimear Lynch, and Petra Collins are offering more nuanced and authentic portrayals of girlhood across photobooks, exhibitions, and digital platforms.”

Tina Barney, The Dollhouse, 1986

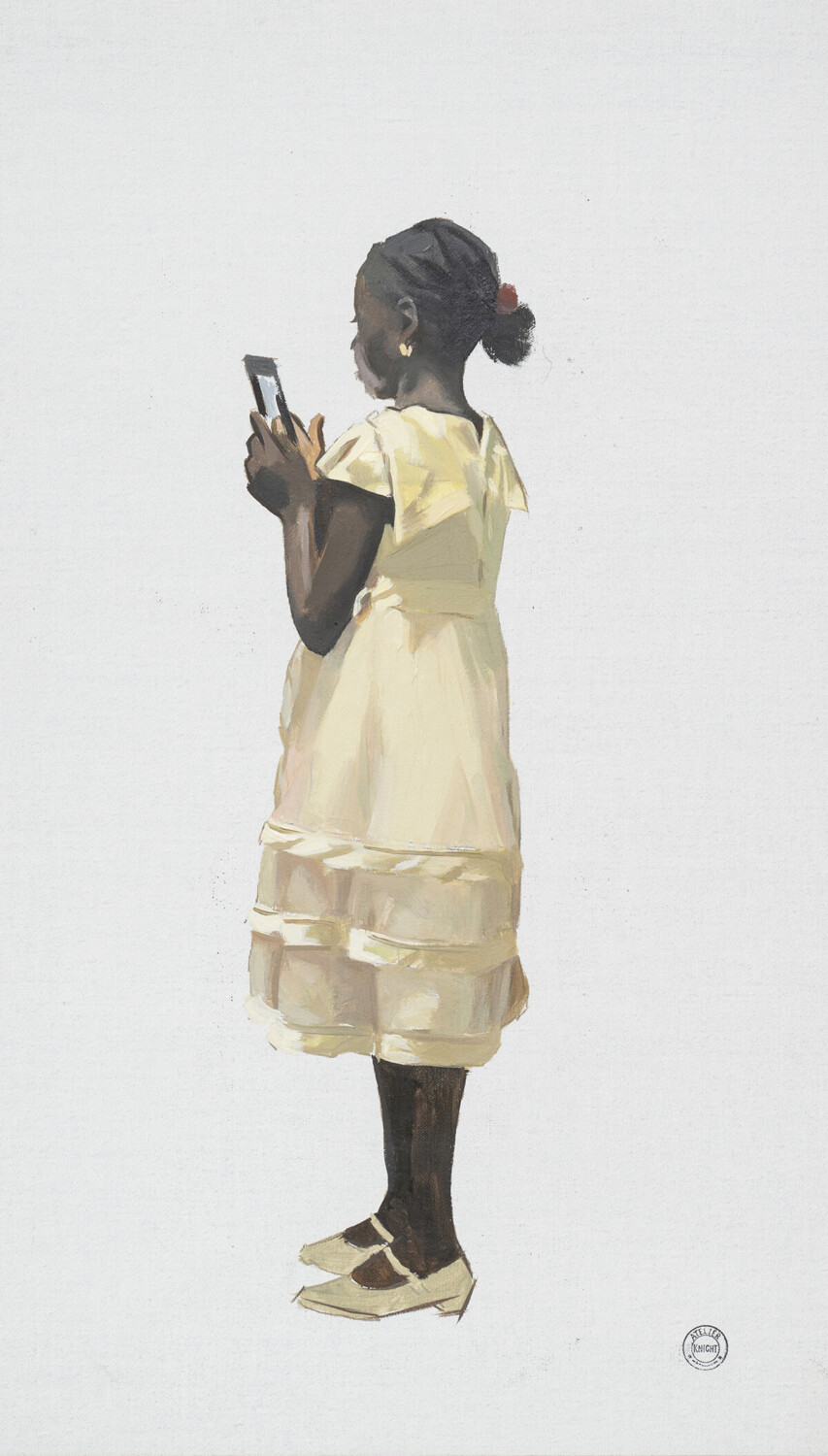

Jas Knight, Croquis for Fugue 14, 2023

Petra Collins in collaboration with JennyFax_I’m Sorry

Eimear Lynch, Girls’ Night (2023)

Harley Weir, I love you as a friend (2025)

The term teenager first emerged as a social and sartorial category in the 1950s, when retailers and manufacturers began to recognize adolescent girls as a powerful consumer group, creating dedicated shopping spaces and sizes. The 1960s youthquake amplified their cultural visibility with miniskirts and mod style, the 1980s and 1990s reframed it through the aesthetics of girl power, and the 2000s turned “girly” fashion into a mix of irony and hyper-femininity, repackaged by fast fashion and global media. “In the 2010s and 2020s, a new generation of designers started crafting their own personal visions of girl and early womanhood, like Simone Rocha, Molly Goddard and Chopova Lowena, Jenny Fax…. Some are inspired by girlhood’s silhouettes, such as the comfort of the baggy shapes of the clothes of childhood, while others reimagine hyper-girlish symbols. The work of these designers disrupts and redefines traditional femininity, moving toward a meaningful reimagining: a girl’s gaze accessible to all ages and genders,” notes De Wyngaert.

Lux’ knitted bikini top and shorts set, worn by the actress Kirsten Dunst. The Virgin Suicides, 1999, Sofia Coppola’s film

Lux’ knitted bikini top and shorts set, worn by the actress Kirsten Dunst. The Virgin Suicides, 1999, Sofia Coppola’s film

Ashley Williams, Spring-Summer 2025

Wales Bonner, Autumn-Winter 2023-2024, Mary Janes

Echoing Judith Butler’s famous line that “gender is a kind of imitation for which there is no original,” girlhood today unfolds in a landscape where imitation and authenticity blur. Tans, eyelashes, lips, breasts, and even personalities circulate as prosthetics for the performance of femininity. To be called “fake” is to risk exclusion — yet the fake is real, shaping intimacy and belonging. “Today, being a teenager often means balancing two identities: how you present yourself in real life and how you perform online. In the exhibition, we show the work of artist Maya Man, who examines internet culture and the performance of self and femininity on platforms like TikTok. Her piece Love/hate confronts public perceptions of young women online, using a video of clips from her own profile displayed on an iPhone attached to a pink ribboned boxing ball. The work captures the complex tensions young women navigate: the constant push and pull between irritation and desire, hatred and admiration.”

Class of 1998, Veronique Branquinho Autumn-Winter 1998 for Self Service No. 8, © Photo: Anuschka Blommers & Niels Schumm

Class of 1998, Veronique Branquinho Autumn-Winter 1998 for Self Service No. 8, © Photo: Anuschka Blommers & Niels Schumm

Class of 1998, Veronique Branquinho Autumn-Winter 1998 for Self Service No. 8, © Photo: Anuschka Blommers & Niels Schumm

Class of 1998, Veronique Branquinho Autumn-Winter 1998 for Self Service No. 8, © Photo: Anuschka Blommers & Niels Schumm

For Elisa De Wyngaert, GIRLS ultimately comes down to this: “The exhibition may be about girls, but it is made for everyone. It was a collective effort between our team, the artists, and collaborators to share and celebrate the layers of girlhood: the memories, the archetypes, the experiences, the obsessions. Above all, I’d hope a teenager walking in — or any visitor, really : ) — comes away with a sense of joy and camaraderie.”

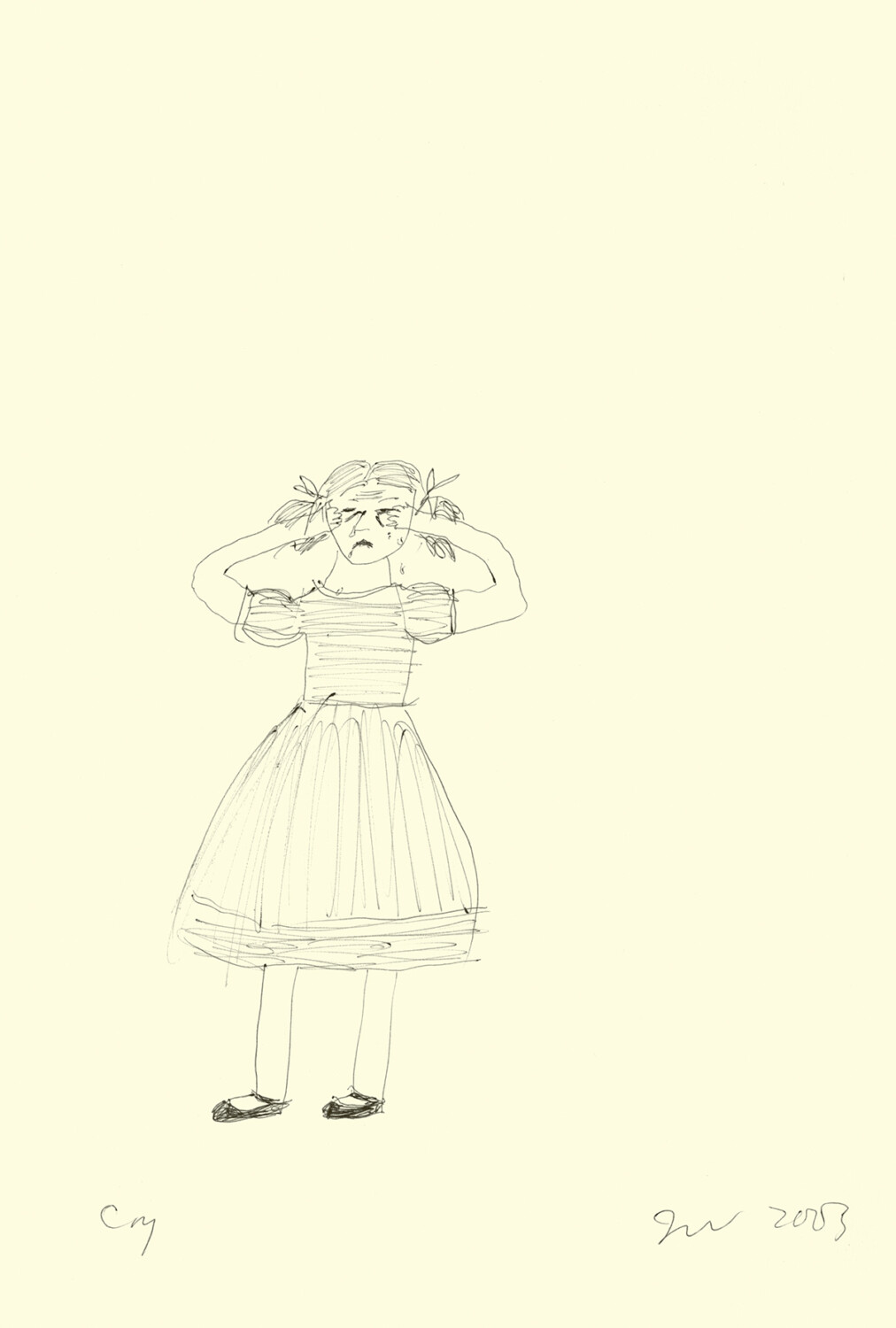

Jenny Watson, Corners of the Heart, 2003

‘GIRLS. On Boredom, Rebellion and Being In-Between’ at MoMu (27 September 2025 – 16 February 2026)

–

Follow us on TikTok @veinmagazine