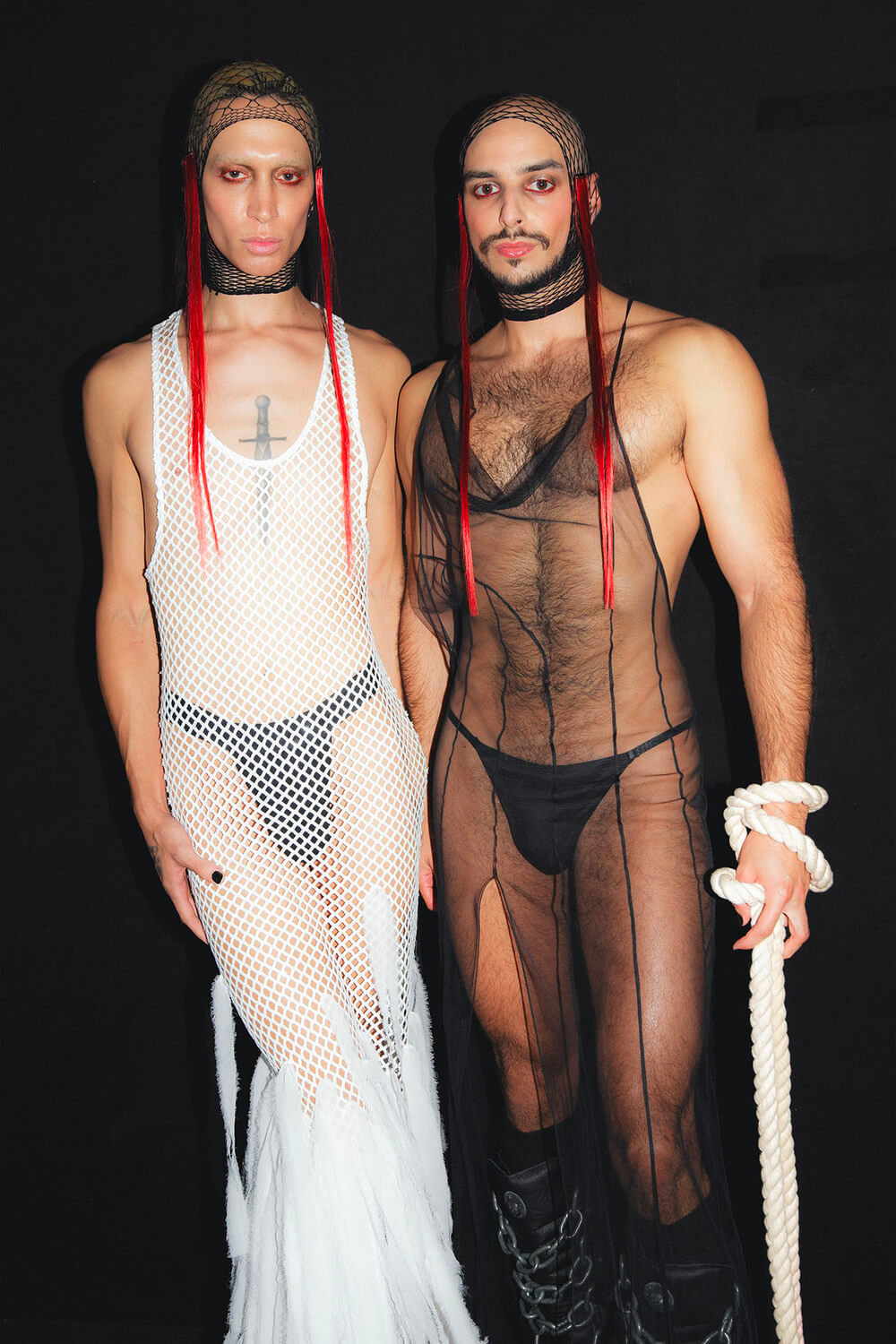

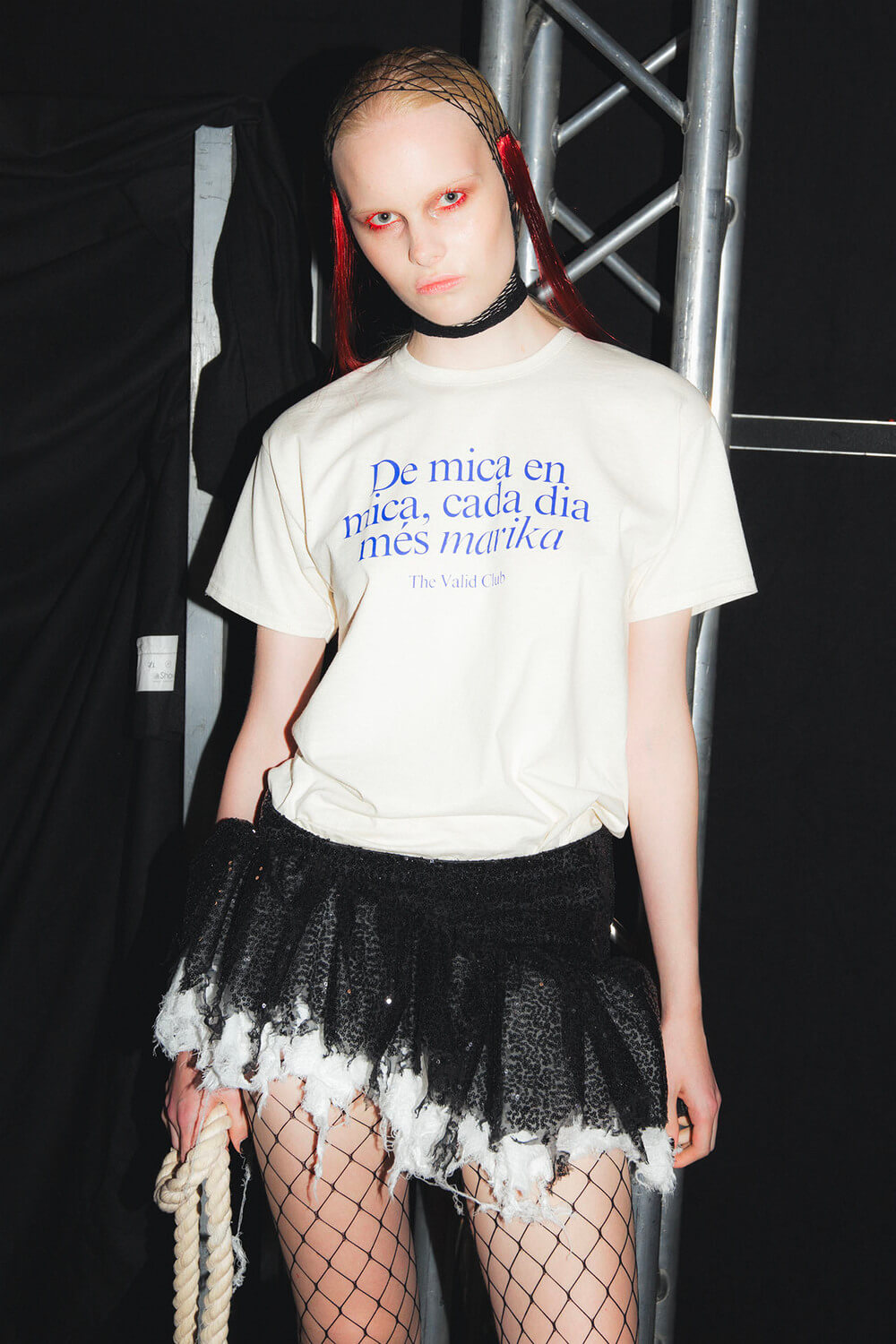

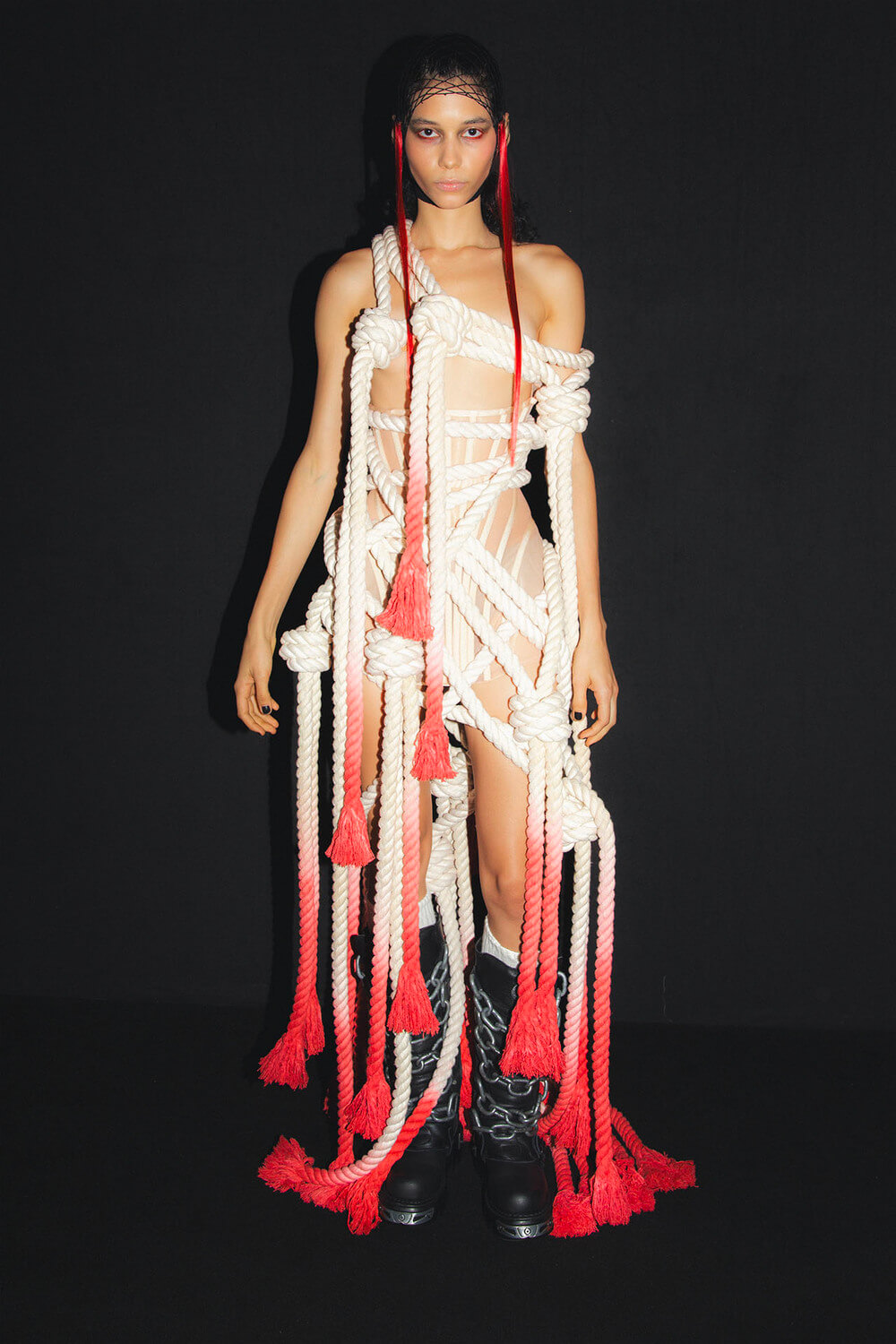

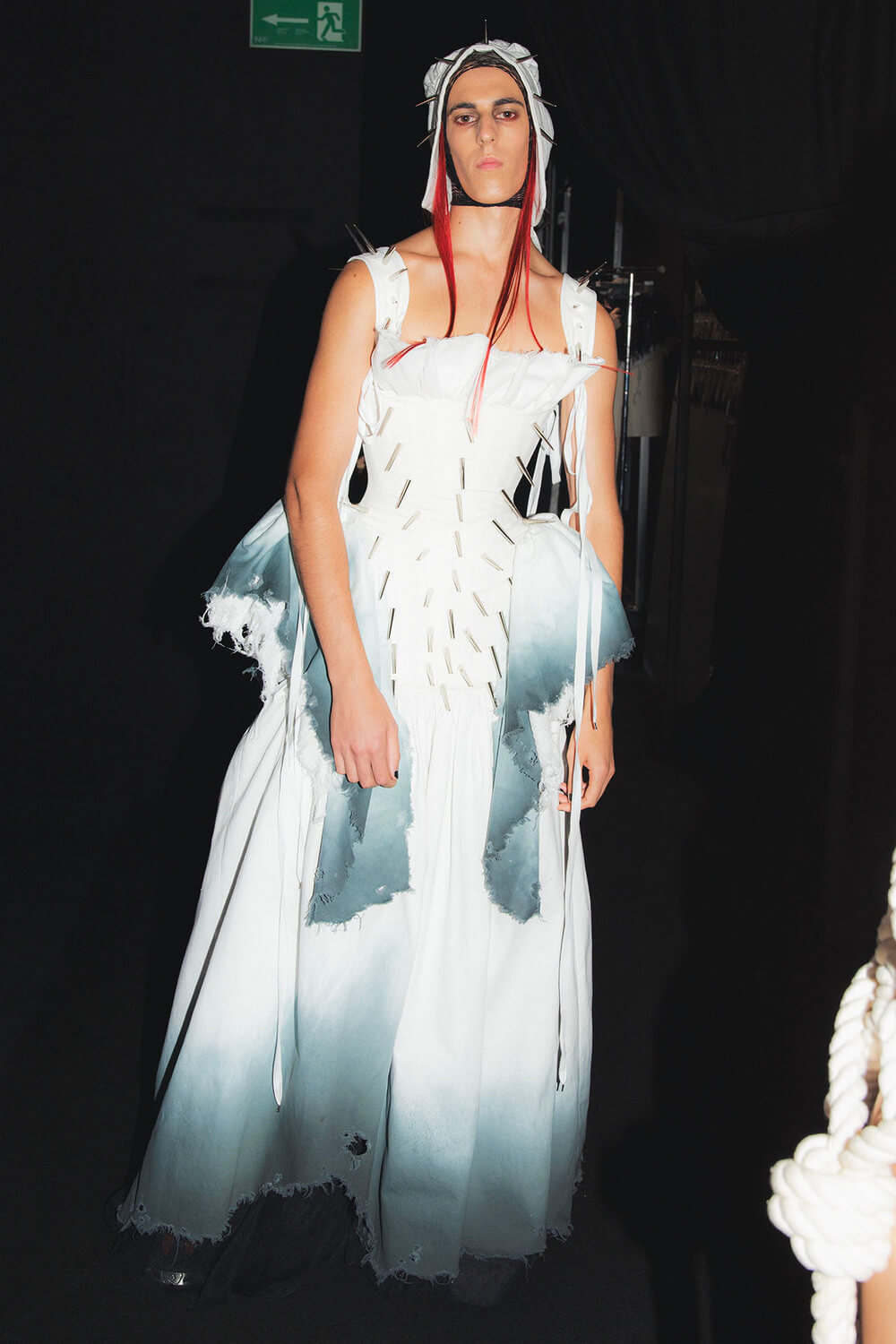

With ‘In Nomine Heretica’, the designer reclaims the symbols of persecution to speak of pride, memory, and identity. A collection that burns softly where pain becomes language, and the periphery, power.

‘In Nomine Heretica’ feels like a spell. A cry from the periphery that summons the memory of witch hunts and the centuries-long persecution of sexual and gender dissidence. With this collection, presented at 080 Barcelona Fashion, Aleixandri Studio turns fashion into an act of resistance, a living archive that stitches collective wounds into strength, transforming pain into power.

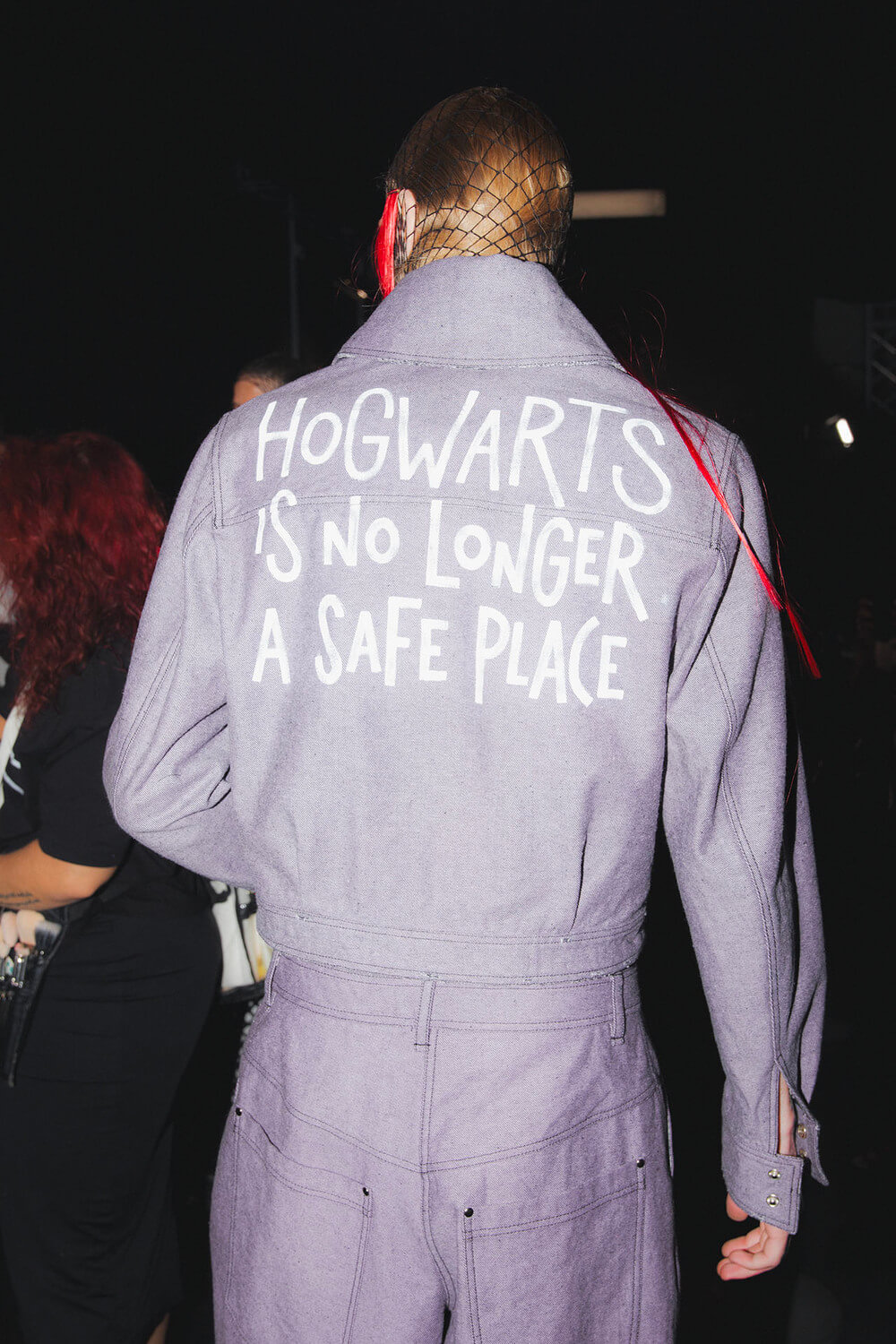

Following ‘Violetas’, the award-winning debut, this new chapter feels sharper, louder, more deliberate. It consolidates the studio’s voice somewhere between critique and tenderness, between inherited pain and the will to repair. Symbols of punishment – the sambenito, the cross, the scar – reappear not as marks of shame but as banners of pride. Where there was silence, now there’s flame.

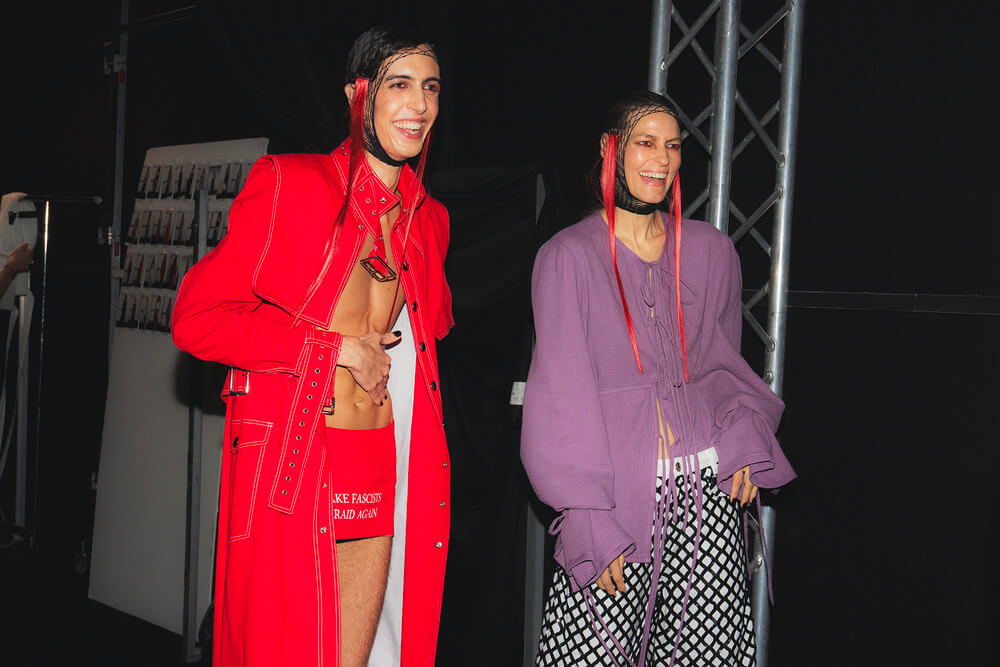

The collection bridges medieval iconography and the queer aesthetics of the seventies and eighties, creating a hybrid language that moves between memory, protest, and beauty. From the periphery, not as absence but as a place of resistance, Aleixandri reclaims other ways of being, creating and seeing. Each garment becomes a contemporary relic, built from repurposed materials and charged with lucid rage and radical tenderness.

At a time when hate speech resurfaces with new faces, ‘In Nomine Heretica’ stands as a body, a gesture and a voice. A collective incantation calling for a future where difference is not persecuted but celebrated. We talked with designer Marc Aleixandri about turning wounds into memory, fashion into resistance, and the power of creating from the periphery. Our photographer, Ángela Ibáñez, takes us behind the scenes of the runway show.

After ‘Violetas’, which was awarded in Madrid, you’re now showing ‘In Nomine Heretica’ at 080 Barcelona Fashion. What does this second chapter represent in your journey as a designer?

It’s quite a big and solid step for the project, one we naturally had to take to consolidate and establish the brand. The first collection was conceived as a kind of introduction, without thinking about its development. This one, however, was created from a different place, already considering its production and continuity in the future.

Why did you choose 080 Barcelona Fashion as the platform to present your new collection?

I think 080 Barcelona Fashion, as a platform, has very clear values and goals that align perfectly with ours.

Also, being a Catalan designer trained in Barcelona, there’s nothing better than presenting my new collection at home.

‘In Nomine Heretica’ builds a bridge between witch hunts and the persecution of queer bodies. In what way do these two worlds speak of the same pain?

Both worlds speak of persecution, abuse, and violence carried out irrationally by the same side. A way of shaping the world based on the desire to erase everything that doesn’t fit into their rigid thinking.

The witches of yesterday are still today’s dissidents.

How do you translate a historical wound like repression or censorship into a contemporary garment?

For me, translating a historical wound into a contemporary garment means revisiting it to turn it into active memory. You can play with symbols, materials, volumes, colors, textures, or finishes that represent that repression or censorship, whether literally or more subtly, manipulating and using them to create garments that speak of the past from the present.

The collection turns pain into pride and shame into a banner. Was it also a personal process of reconciliation?

It was more a need to shout. I needed to speak about the situation we’re living in, and the best way I know how is through fashion and my designs.

You use symbols like the sambenito, the stake, or the scar. How did you decide which iconography to rescue and how to update it?

I decided to bring back the most representative symbols from the story I wanted to tell, so that ’In Nomine Heretica’’s message would be as clear as possible.

The sambenito, for example, has been one of the main elements. It appears in some garments more subtly, by reinterpreting its square silhouette in shirts or trench coats, and also more literally in one of the looks.

The red cross on a white background felt visually very powerful to me. Besides, even today, people in the LGTBIQ+ community still carry that same ’sambenito’ for our identities. That’s why, on top of the cross, there are 65 tally marks. They speak of persecution, of punishment, of the 65 countries that still criminalize belonging to the community in some way.

What would you like someone to feel when wearing a piece from ‘In Nomine Heretica’?

I’d love for them to feel that power of resistance and, in a way, that thirst for revenge.

Your work approaches fashion as a living archive. What role does memory play in your creative process?

I believe that remembering and revisiting the past helps us understand the present. It’s fascinating to see all the parallels between historical and current events. They say learning from the past helps us avoid making the same mistakes in the present, but some prefer to ignore that.

How do you approach patternmaking so it’s inclusive and adaptable to diverse bodies without losing precision or visual poetry?

Patternmaking, for me, is still part of the design process.

The main idea is to work with the volumes, resources, and silhouettes of the garments so they can be worn by different bodies, regardless of gender. It’s a constant exercise: testing garments on bodies with different anatomies, analyzing how they behave, and turning mistakes into a conscious part of the design.

You worked for five years alongside Palomo Spain, participating in projects with Beyoncé and Rosalía. What did you learn from that world that now resonates in Aleixandri Studio?

I learned a lot. I always say it was like a second degree for me. I worked with materials and techniques I’d never used before, on very different projects with different needs, and I took something valuable from each of them. As creative people who love to see, try, and make things, we’re a bit like sponges. It’s inevitable to absorb elements from every place we go, whether technical, aesthetic, or emotional. Combining all those references with our own voice is what gives us identity in a world where everything has already been invented.

Aleixandri Studio defines itself as a space that creates from the periphery. What does that word, “periphery,” mean to you?

Periphery, for me, is not a place of lack but of resistance.

From there, you can look at the center with critical distance, question what’s established, and create new languages. Working from the periphery means not aspiring to fit in, but reclaiming other ways of being, creating, and existing.

In the case of Aleixandri Studio, the periphery is both a political and emotional stance. It’s about creating from queerness, from the wound and from memory, transforming them into strength, beauty, and future. And even though fashion is what I’m passionate about and I don’t know how to do anything else, I also despise the fashion world as it’s mostly built: hierarchical, exclusionary, superficial. Sometimes I have to step into it, and I don’t feel comfortable there. Maybe that’s why I try to work from the outside, to reimagine it from another place.

The garments are made from deadstock and repurposed materials. How does that ethical decision influence the visual narrative of your collections?

It’s an ethical decision, but also a practical one.

Many times you have to make decisions and adjust your vision depending on the resources available at that moment. Maybe you have something very clear in mind and you have to adapt it, or just put it away in a notebook and hope to make it someday. But I don’t see that “lack” of resources as entirely negative. It opens the door to creativity even wider, helps you become resourceful, and pushes you to do the most with the least.

In a political context where hate speech is resurfacing, do you think fashion has a specific social responsibility?

It would be utopian to assign a specific social responsibility to fashion as a whole. At the end of the day, it’s still an industry, and within it there are many different realities. Some people don’t feel comfortable with that weight, or simply aren’t affected by certain forms of violence or situations, and therefore don’t feel compelled to take on that responsibility.

That said, I do think that if we have a voice or a platform within this system, no matter how small, we can use it. In my case, I can’t (and don’t want to) separate the designer from the person. For me, fashion can’t be empty of content or position. Everything I do comes from a political, emotional, and collective perspective, even if sometimes it manifests itself more subtly and other times in a more openly combative way.

What role does sensuality play within such a political narrative?

I think sensuality in my work doesn’t come from desire, but from reclaiming. When I use transparencies or reveal the body, I don’t do it from an erotic gaze, but from the need to give value, presence, and power to bodies and identities that have historically been hidden or censored. No matter how sensual it may appear, my intention is not to provoke desire, but visibility and dignity.

Photography by Ángela Ibáñez for VEIN MAGAZINE

Follow us on TikTok @veinmagazine