Vivienne Westwood and Rei Kawakubo share a radical approach to fashion that challenges conventional ideas of the body, taste and beauty, reworks historical sartorial codes and absorbs punk as a disruptive language. Now in dialogue in ‘Westwood / Kawakubo’ at the NGV, in #VEINDIGITAL we speak with the curators about shared ground, key differences and lasting influence.

Westwood / Kawakubo proposes a dialogue between two designers who, from different contexts and strategies, reshaped fashion as a critical practice. Vivienne Westwood turned clothing into a site of political confrontation, using history, tailoring and punk iconography to question power, class and gender. Rei Kawakubo, meanwhile, absorbed that disruptive energy and redirected it toward a more abstract investigation of form, volume and the relationship between garment and body, pushing fashion beyond representation and into conceptual territory.

Rather than tracing a linear story of influence, Westwood / Kawakubo, presented at the National Gallery of Victoria in Melbourne, examines how both designers worked in parallel, sharing a commitment to breaking conventions while developing radically distinct languages. Their practices challenge fixed ideas of taste and beauty, redefine the body as something unstable and mutable, and treat history as material to be reworked rather than referenced. In #VEINDIGITAL, we speak with the curators, Katie Somerville and Danielle Whitfield, about these points of contact and divergence, and about the lasting impact of both designers on contemporary fashion.

The use of torn fabrics and distressed materials had clear precedents in Westwood, where they functioned as a direct visual language of protest. How did Kawakubo transform those same signs into a different way of thinking about clothing, form and meaning?

In the mid-1970s, Westwood, along with her then-partner Malcolm McLaren, helped to formulate punk style: rips, tears, tartan, bondage-wear and confrontational graphics transformed clothing into protest – emblems of anarchic, anti-authoritarian style. In the 1980s, Rei Kawakubo’s runway collections were equally revolutionary for their anti-fashion aesthetics. In contrast to the prevailing trend of bodycon styles and high glamour seen on Paris catwalks, the garments designed by Kawakubo were unorthodox, oversized, purposely distressed and predominantly black. She disregarded symmetry and perfect fit, instead creating clothes that enveloped and concealed the body. She also drew from Japanese principles such as wabi-sabi, a philosophy that encourages respect for humble materials, imperfection and the patina of age.

Comme des Garçons jumper from the ‘Holes’ collection, autumn–winter 1982–83. Photo © Peter Lindbergh.

Westwood’s punk introduced a visual language of rips, imperfection and DIY gestures that resonated in the early years of Comme des Garçons. To what extent do you think this impact shaped Kawakubo’s initial creative world?

I think Westwood’s desire to rewrite the rules of dress, her involvement with punk, and her iconoclasm was hugely influential on the fashion world, including Kawakubo. Kawakubo has stated, “I’ve always felt an affinity with the punk spirit. I like that word. Every collection is that. Punk is against flattery, and that’s what I like about it.” Punk tropes and a punk ethos infuse many of her collections and her approach to making. However, in the 1970s Kawakubo also said, “I make clothes for a woman who is not swayed by what her husband thinks.” Her creativity was also fuelled by a reaction against restrictive societal conventions and limiting notions of beauty, taste and gender.

Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren, ‘Nostalgia of Mud’, autumn–winter 1982–83. Photo © Robyn Beeche.

In Westwood, punk signs were direct: bondage, offensive graphics, DIY alterations, distressed textures, tartan. In Kawakubo, confrontation emerges more through form, volume and the negation of the silhouette. What does this difference reveal about the kind of provocation each one pursued?

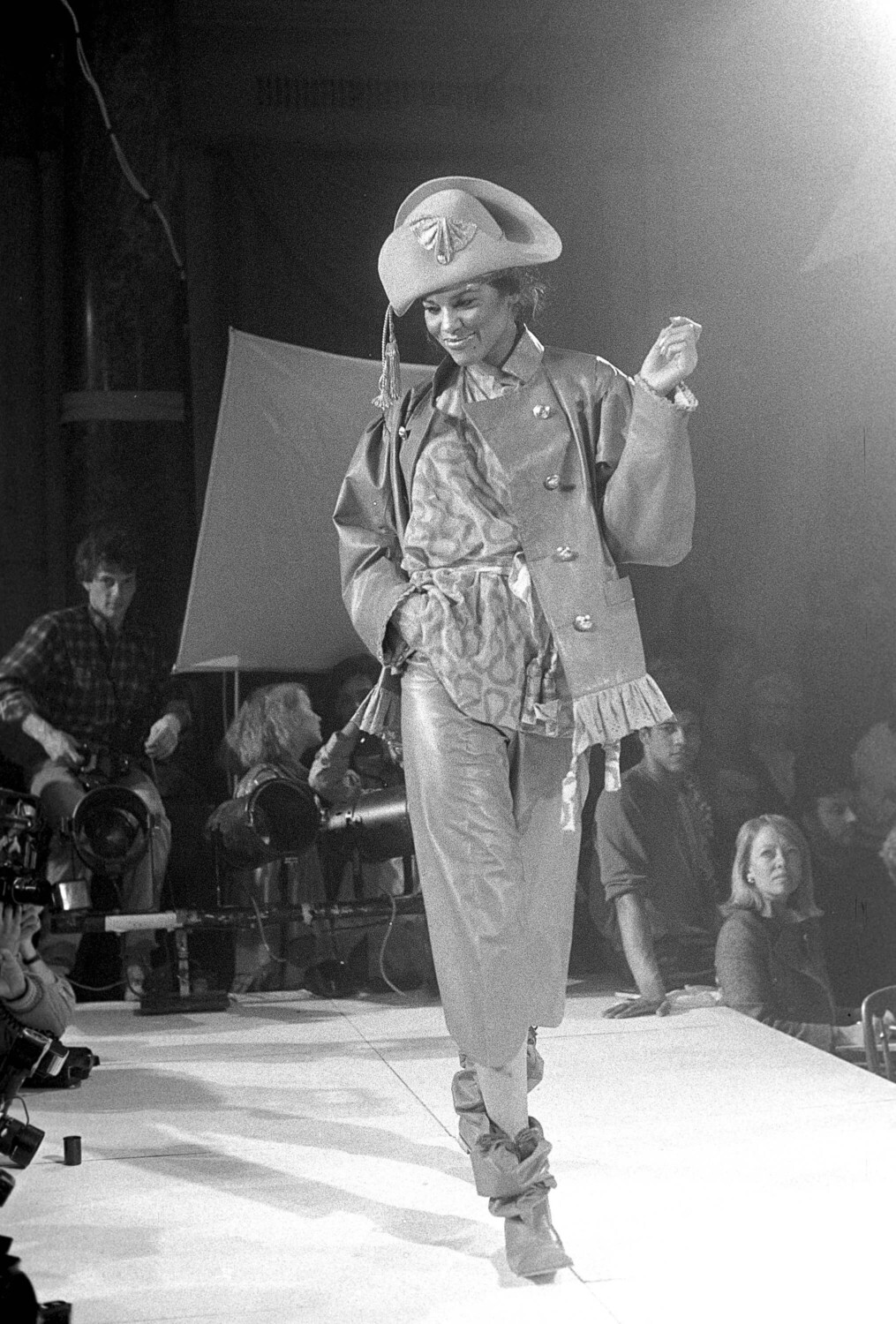

Neither designers’ output should be reduced to their relationship with punk style and aesthetics. In 1981, Westwood broke away from punk, presenting her first runway collection in London, ‘Pirate’. She turned to fashion history, particularly historical menswear, exploring seventeenth- and eighteenth-century silhouettes, portraiture and the dress of highwaymen, buccaneers and dandies. Every collection since has been about developing and evolving her design vocabulary, continuing to question and resist fashion convention. Think about collections like Punkature or Hypnos, her use of corsetry, her interrogation of Britishness, or tailoring conventions and her activism of her later years.

Similarly, Kawakubo’s entire output since the early 1980s has been a search for things that do not exist. Over her five decades in fashion, this modernist spirit and her commitment to the new and original has been realised through experimental patternmaking, the creation of specialist textiles, deconstructionism, her continual questioning of clothing form and function, and her interrogation of gender codes and the boundaries between body and dress. There are many challenges to what we think of as fashion, especially since 2014 when she has sought to ‘break the idea of clothes’. The designers tackle similar themes in their work, but they execute them completely differently. They also have concerns that are specific to their own set of values.

‘Pirate’, Vivienne Westwood, autumn–winter 1981–82. Photo © David Corio / Redferns via Getty Images.

‘Ceremony of Separation’, Comme des Garçons, autumn–winter 2015–16. Image © Comme des Garçons.

‘18th-Century Punk’, Comme des Garçons, autumn–winter 2016–17. Image © Comme des Garçons.

The body is central to both their practices. In what ways would you describe the difference in how Westwood and Kawakubo conceive, treat or reformulate it?

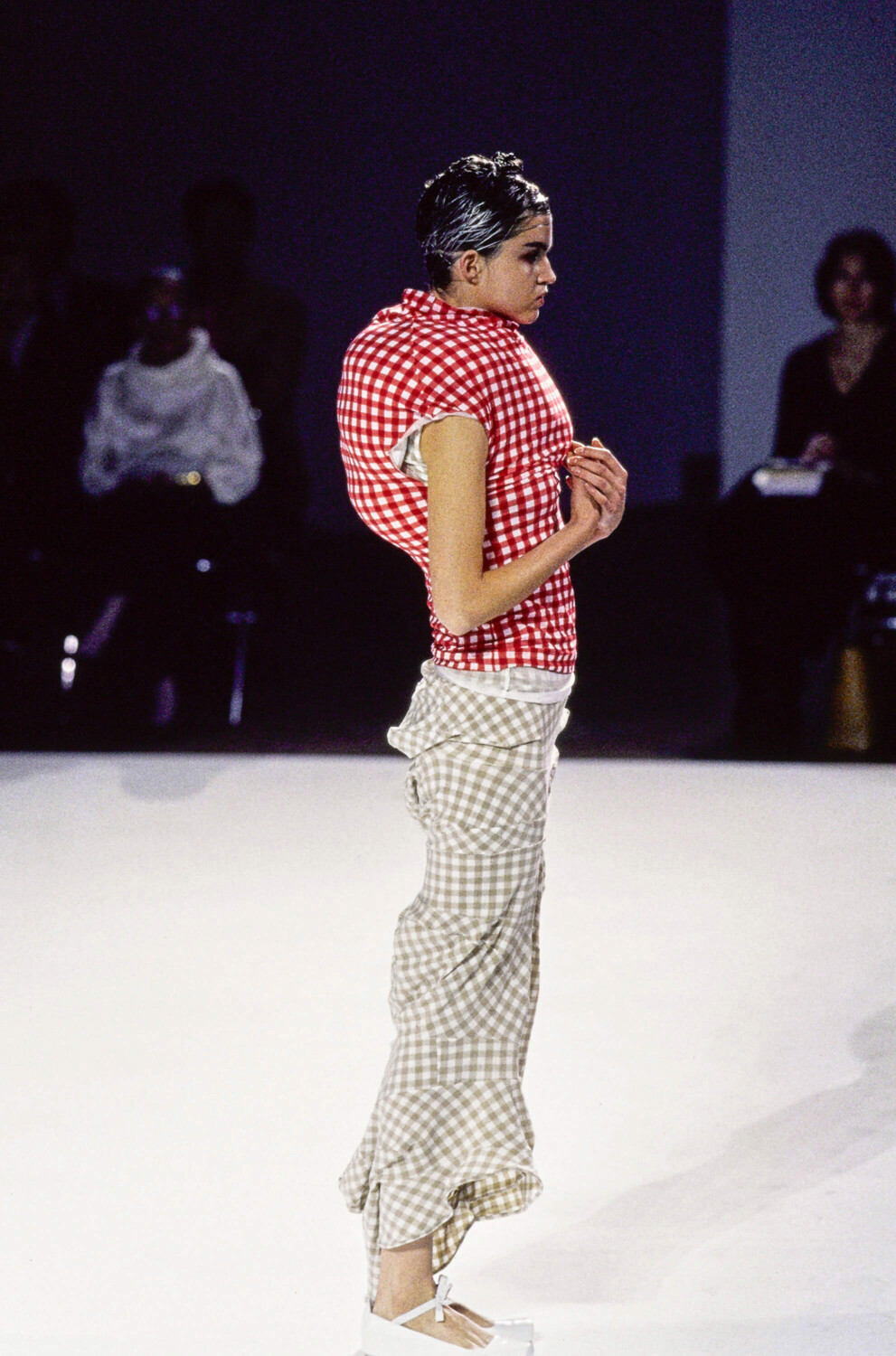

Across their careers, Westwood and Kawakubo have reimagined the relationship between fashion and the body. In distinct, but equally radical ways both have questioned social constructs, challenged fashion industry standards, and explored the tension between freedom and constraint, comfort and objectification. For Kawakubo’s Body Meets Dress–Dress Meets Body collection, presented in 1996, she used irregular padding to distort the silhouette and blur the boundary between body and garment. In 2012, she used two-dimensional pattern-cutting to create ‘flat’ clothing that disregarded the contours of the body altogether. Most recently, her collections have evolved into ‘wearable objects’: extreme, sculptural works that abandon comfort and function to critique socially constructed ideas of clothing forms and beauty.

‘Body Meets Dress–Dress Meets Body’, Comme des Garçons, spring–summer 1997. Image © Comme des Garçons.

Westwood has similarly contested precepts of sexual expression and the ‘fashionable body’ but did so through irony and exaggeration. Rejecting the minimalist ‘waif’ aesthetic of the early 1990s, she created hyper-feminine silhouettes through padding and compression, infusing her designs with a provocative sensibility. By bringing historical undergarments such as the corset and bustle to the outside, Westwood both exposed and satirised the artifice of femininity, transforming it into a form of sexual agency.

‘On Liberty’, Vivienne Westwood, autumn–winter 1994–95. Photo © Guy Marineau.

In what ways do Vivienne Westwood and Rei Kawakubo continue to shape the work of designers and younger generations today?

Through their pioneering concepts and innovative design methods, they have changed the way that we think about fashion. They have shown us the power of fashion to protest orthodoxy, whether in Kawakubo’s case by setting out to ‘make things that did not exist before’, or in Westwood’s by reinterpreting the past, setting precedents that have recalibrated how we think about things like beauty, the body, agency, and identity.

To put that in clothing terms, think about the impact of Kawakubo’s use of black, distress and asymmetry, her deconstructionism and her bodily abstractions, or think about Westwood’s innovative use of underwear as outerwear – her corsets, crinolines and bustles. Each have challenged our ideas about dress.

‘Portrait’, Vivienne Westwood, autumn–winter 1990–91. Photo © John van Hasselt.

‘Anglomania’, Vivienne Westwood, autumn–winter 1993–94. Photo © Sheridan Morley.

‘Blue Witch’, Comme des Garçons, spring–summer 2016. Image © Comme des Garçons.

‘Uncertain Future’, Comme des Garçons, spring–summer 2025. Image © Comme des Garçons.

For more information about Westwood / Kawakubo, visit the National Gallery of Victoria website. The exhibition is on view until 19 April 2026.

–

Follow us on TikTok @veinmagazine