Lamine Badian Kouyaté, widely known as XULY.Bët, is a Malian fashion designer whose creative vision has been influential in pushing the boundaries of what fashion can be, especially with regard to sustainability, identity, and street culture. Born in Bamako in 1962, he moved to Paris in the 1980s after studying architecture. He founded his label XULY.Bët, “Keep your eyes open” in Wolof), in the early 1990s.

In 1996, when he won the prestigious ANDAM award, which provided crucial support to help mass-produce some of his designs that previously had existed only as one-of-a-kind pieces. Kouyaté become the first African designer officially included on the Paris Fashion Week calendar, recognized by the Fédération de la Haute Couture et de la Mode. Azzedine Alaïa, who was Tunisian, actually came before Kouyaté in terms of presence in Paris fashion, but Alaïa was not officially on the Paris Fashion Week calendar for much of his career as he preferred to show on his own terms often off calendar, rejecting the rigid fashion schedule. In the same ways, we can say that Alaïa’s approach is what also kept the business and creativity going.

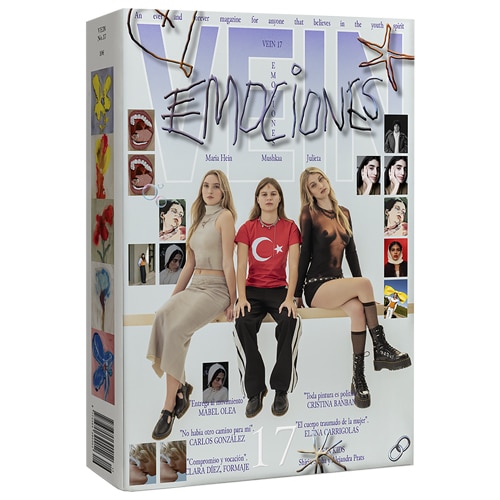

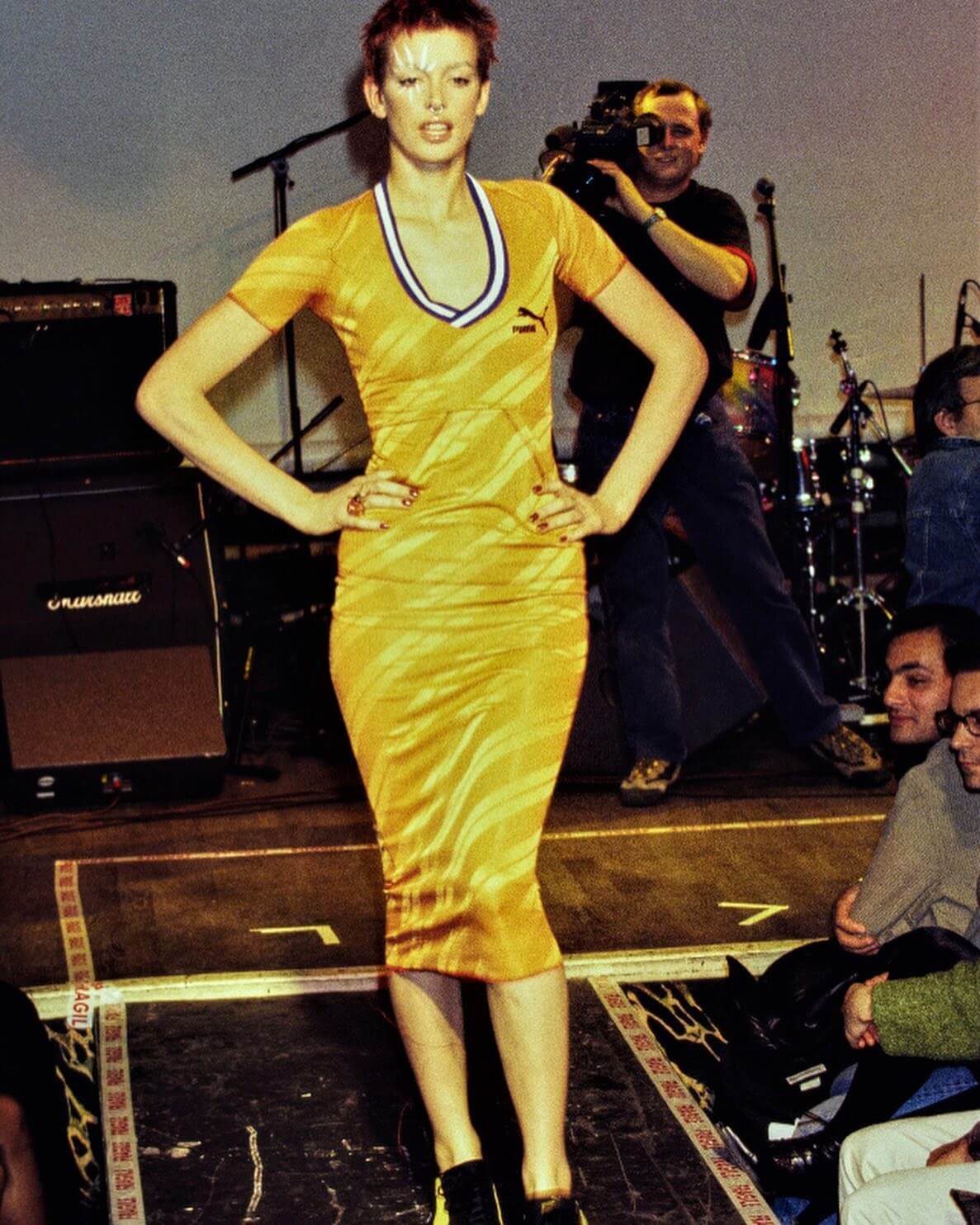

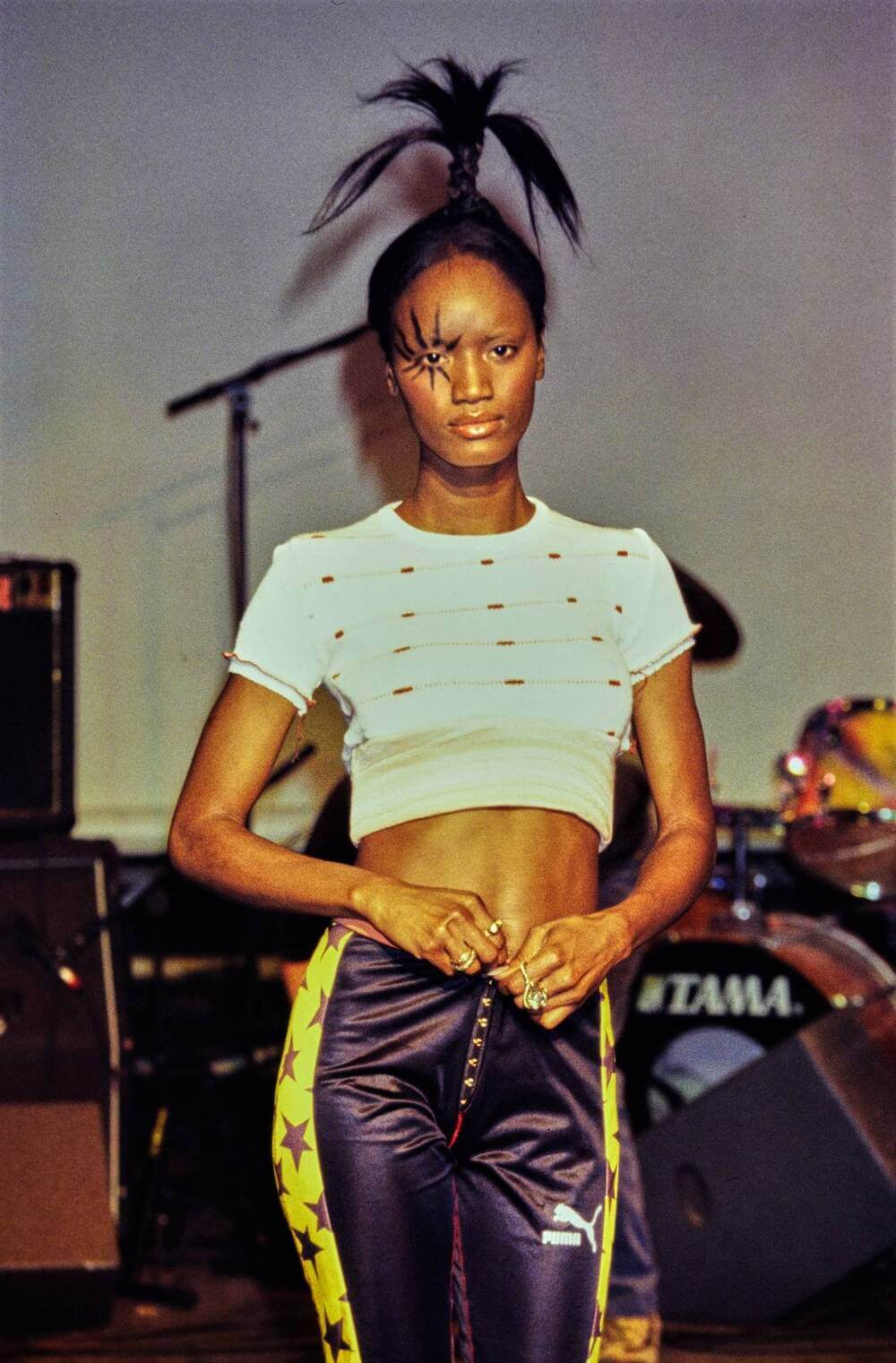

XULY.Bët x PUMA SS95

XULY.Bët’s recognition came after earlier successes by that time, the brand was had already stocked in boutiques in Paris and New York, had been named “Designer of the Year” by the New York Times, had done collaborations (including with Puma), and had built a reputation for upcycling, bold color, and reinventing discarded materials. Off and on, over three decades, his fashion shows have been more of moments of community, performance, and counter-culture, giving voice and visibility to Black, immigrant, urban youth that were often sidelined in mainstream Paris fashion.

XULY.Bët x PUMA SS95

Despite his early prominence, XULY.Bët has frequently been under-recognized in fashion historiography and popular memory. Much of his most groundbreaking work was done in the pre-Internet era, before social media and digital archives made visibility easier. Kouyaté often resisted or found difficulty working within the structures of large fashion houses or commercial systems that prioritize mass production, big marketing budgets, and profitability over experimentation. This made it harder for his innovations to be sustained or scaled as widely as some contemporaries. Being African (Malian origin), working with recycled materials, operating somewhat “underground” or off schedule, focusing on cultural identity outside traditional European luxury norms are things that the fashion establishment has historically undervalued. Racism, Eurocentrism, and a preference for polished, commercial designs have contributed to his being less institutionally recognized. For me, a fashion student in the early 00s in Paris, XULY.Bët was the Demna before Demna, he was what the cool kids wore and so many of us fashion students wanted to work for him. He created a look that was instantly recognizable, but with joy not cynicism or even sinister undertones.

Over the years, his presence in major fashion week calendars, large retail partnerships, and media coverage has waxed and waned. Some of his collections became more sporadic with many shows “off schedule,” parallel, or more community-based, rather than high-budget runway productions. In fashion you need to sell, but there is also something cool about never selling out. Shayne Oliver has often cited Lamine Badian Kouyaté’s work as an early example of radical Black creativity within the European fashion establishment. XULY.Bët’s DNA runs through much of the progressive fashion that arouse out of the 2010s, from Marine Serre’s eco-futurism to Virgil Abloh’s conceptual remixing and Grace Wales Bonner’s poetic identity work. Into the 2020s, his ideas from recycling, cultural fusion, to radical inclusivity have shaped the way designers now understand what “the future is now” fashion truly means.

Photographer Denzil Jacobs captured Xuly Bët’s Spring Summer 2026 show at Paris Fashion Week back and front stage pulsed with raw energy and cultural pride, this pride was a melting pot, of anyone celebrating resilience. The atmosphere felt like a block party meets protest with each model coming out to dance. The climax came when French Caribbean singer Maureen closed the show, radiating power in a red reworked ensemble, turning the runway into a dance floor and sealing the collection as a statement of freedom, community, and enduring cool.