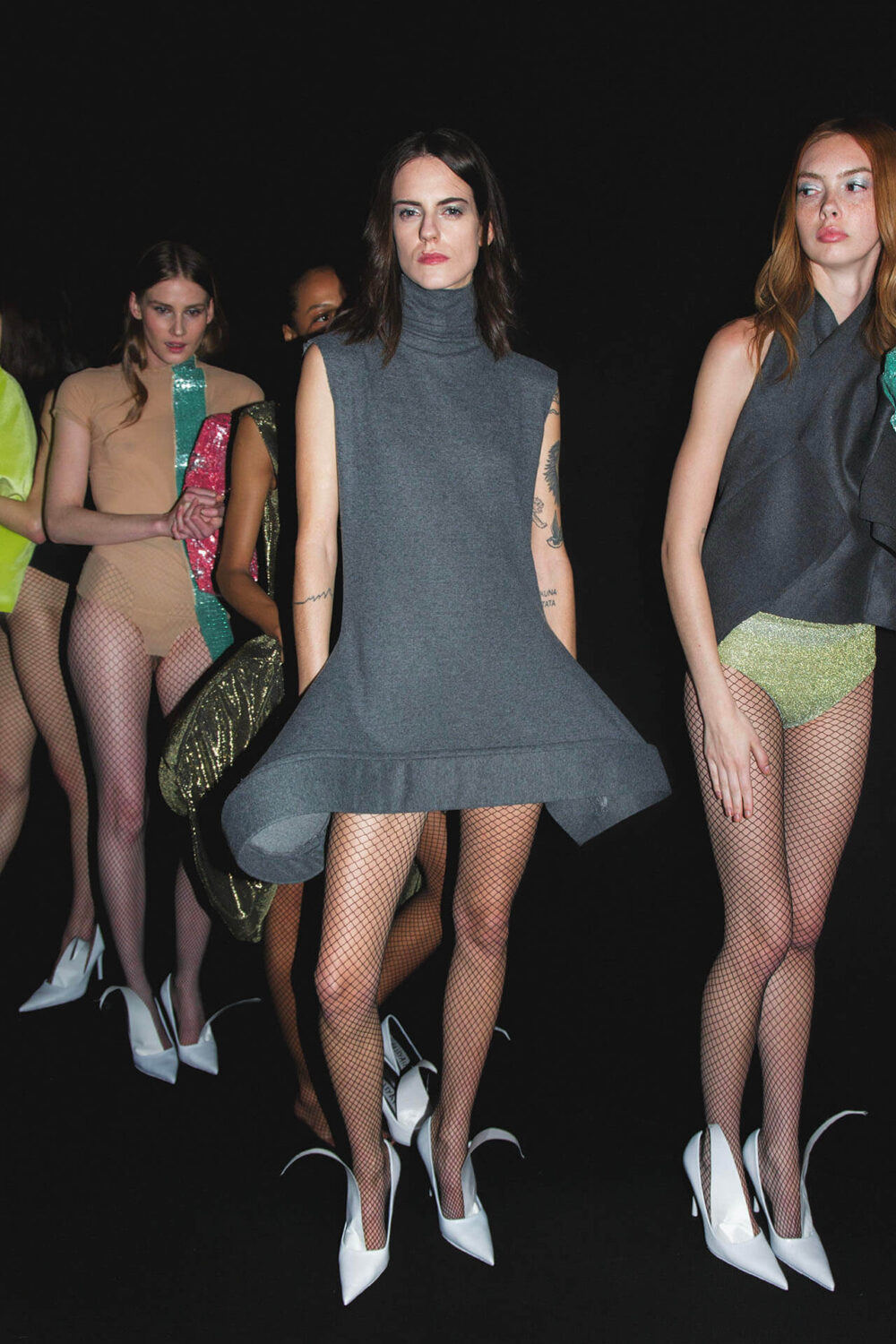

The Spanish designer debuts at 080 Barcelona Fashion Week with a collection that explores minimalism as a language of expression and process art as a manifesto of transformation.

Known for his sculptural tailoring and poetic defiance of convention, Ernesto Naranjo makes his debut at 080 Barcelona Fashion with 014, a collection where theatrical nostalgia meets elastic-fueled surrealism. Inspired by the opulence of the Ziegfeld Girls and the dreamlike chaos of artists like Leonora Carrington and Lynda Benglis, the designer builds garments that twist, bounce and reshape themselves with a wink – all while holding tight to technical precision.

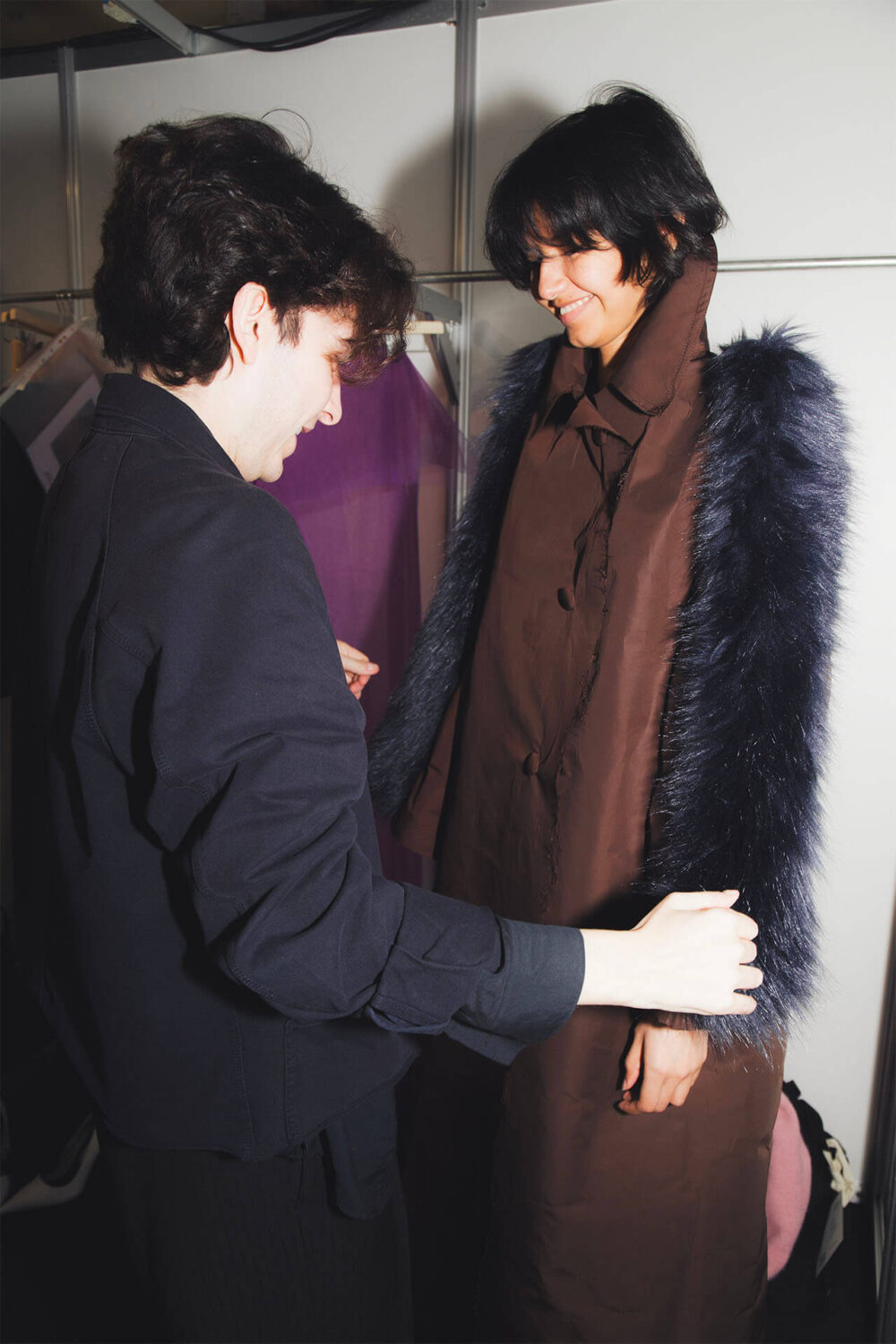

But behind the fantasy lies strategy. A Central Saint Martins graduate with experience at Maison Margiela, he approaches the catwalk as both stage and showroom. His pieces don’t just perform – they hold their own off the body too, as sculptural objects with intent and soul. Each look is infused with movement, irony and an undercurrent of joy – a reminder that fashion can still surprise, amuse and challenge without losing its elegance.

We spoke with Naranjo about craftsmanship, contradiction and the enduring value of creating clothing that resonates both emotionally and intellectually.

This is your first time showing at 080 Barcelona Fashion. Why did you choose this platform to present your new collection?

I chose this runway because I’ve been watching it grow in terms of visibility, both nationally and internationally. Plus, the whole ecosystem of influencers and social media fits really well with my brand and aligns with where I’m at right now – on the rise and aiming to solidify my presence in the international market.

We wanted to make sure it was the right time to really make the most of the opportunity. This season also feels special because I’ll be sharing it with fellow designers from Madrid. A lot of us have chosen to show at 080 this year, and I’m genuinely excited to see what everyone else brings to the table.

How do you manage to make unexpected volumes work within a clean, conceptual aesthetic?

When we work with patterns and garment structures, I always like to break things apart, distort them, or bring out a playful side. I love starting from everyday pieces – a T-shirt, a pencil skirt, a Barbour-style jacket – and using familiar wardrobe elements to transform them through fabric and pattern structure. We do this with elastics, boning, and materials that wouldn’t typically belong to those garments or shapes, which creates an interesting, playful kind of tension.

How do you reinterpret the theatricality and glamour of the Ziegfeld Girls through a contemporary and minimalist lens in ‘014’?

This year I’ve been watching tons of old Hollywood films, and I got completely fascinated by the theatricality, the glamour of the musicals, the Ziegfeld Girls, and the way those shows were put together. I loved it, but at the same time, I found them a bit too rigid and stiff – especially in terms of movement. So I wanted to bring that aesthetic into a softer, lighter space when creating the looks.

The collection has a lot of movement, but it’s movement with a touch of humor. The garments seem to bounce, almost like they’re jumping, creating this cartoonish dynamism that takes you into a more surreal world.

To unify everything, we looked at how those musicals were very maximalist in costume design. We played with that – used the shine, the metallic structures, the volume-building elements – but always through fabric manipulation and tailoring techniques, like inner elastics in the skirts or corset boning. The key was placing them in unexpected areas, where they don’t traditionally go, to create new structures and volumes while refining the overall visual message.

What drew you to the work of Carrington and Benglis to explore the duality between the dreamlike and the sculptural in this collection?

What really struck me was the contrast between the two. Within their creative worlds, both artists push us out of the ordinary using their materials and narratives. Benglis does it in a rawer, more instinctive way, while Carrington comes from a fantastical, dreamlike, and often ironic perspective, creating visual worlds that feel completely out of the norm.

I wanted to blend those two energies: Carrington’s attention to detail, her characters and aesthetics that feel straight out of surreal fairytales; and from Benglis, I was mostly inspired by her sculptural work – how she twists, turns, and mixes materials, letting them expand into space and create dialogues. That idea of spatial intervention really speaks to me, and that’s also how I treat my garments – altering them with distorted sewing elements that break away from convention.

What role does irony play in the development of your pieces and the visual narrative of the collection? Where can we see it?

The irony and surrealism come from using materials or design elements that you wouldn’t typically associate with garments – or by placing them completely out of context. We take materials to places they don’t usually belong. For instance, instead of using inner tulle to give volume to a skirt – as you traditionally would – we use elastic bands or corset boning. And it’s those very boning pieces that create tension between fabric and volume, building unexpected structures and outcomes that defy conventional tailoring logic.

What do you hope to provoke in the audience by creating that tension between the ordinary and the fantastic?

First and foremost, I want the audience to enjoy themselves and have a good time. I always remember something my professors at Central Saint Martins used to tell us: “Have fun!” To me, that means not taking ourselves too seriously. At the end of the day, fashion is also meant to be fun, right? Of course, it’s a business, and it has to be profitable, but if we don’t enjoy what we create, we’ll never be able to convey anything.

In ‘014’ you create a dialogue between past and present. How do you combine the traditional with the contemporary, and what challenges does that involve?

Combining the traditional with the contemporary creates a kind of tension that I find really exciting. It’s about taking something familiar to the viewer and translating it into your own language. You use a safe element, something they recognize, as a way in.

Take a jacket or a trench coat – garments we see on the streets all the time. You can alter that recognizable silhouette by adding disruptive elements within the design. That way, the viewer connects with it because it feels familiar, but also senses that something’s different. From there, they might be more open to your message.

How do you balance the conceptual with the wearable in each collection?

I’ve always said that wearability depends on your context, your environment, and how you intend to use a garment. The idea of what’s commercial really depends on who’s in front of you and who’s wearing the piece. For someone who collects art or couture, a white shirt might not seem very commercial. But for someone who shops high street fashion, it’s the most commercial thing in the world.

So we need to rethink the idea of what’s commercial and stop fearing it. You have to know what your product is and who it’s for. Sometimes fashion and art overlap, and I have many clients who are looking for exactly that – something beautiful, rare, and emotionally stirring. Sometimes they buy it for a special occasion, and other times just because they want to enjoy looking at it.

You say each piece is conceived as ‘a work in constant evolution.’ Where would you like to see Ernesto Naranjo evolve, both as a brand and as a designer?

Ernesto Naranjo is a small, niche brand. I’d like it to grow, but always with a clear vision. I always reference Dries Van Noten. I remember an interview he did with Tim Blanks where he said that consistency over time is more important than highs and lows. That stuck with me and really shaped how I think about building a brand. My idea is to grow steadily. That’s also something I learned from John Galliano while working at Maison Margiela. After his journey through Dior and his own label, he always said: step by step. That really stayed with me.

It’s also important to understand that fantasy and influencers are great, but a brand can’t survive on communication alone. At the end of the day, there are real clients and consumers, and we need to offer pieces that truly appeal to them. For me, it’s essential that when we put on a show, and the clothes are hanging on the rack before hitting the runway, they already speak for themselves. They don’t need a body to make sense. They should be desirable objects in and of themselves.

What elements of your time at Maison Margiela under Galliano’s direction still shape your creative process today?

My time at Maison Margiela was incredible, but also very intense. We worked long hours with an obsessive focus on every detail and every aspect of what we did. That’s one of the most important things I took away from it – that you need to be at least a little obsessed with your craft. That’s what gives meaning to the work.

But I also learned something just as valuable: that fashion isn’t everything in life. As designers, we’re passionate about what we do, but it’s crucial to separate personal life from work and take care of both. I’m still working on that balance so both sides can thrive.

Creatively, I learned so much. What stuck with me most from Galliano is how everything you see on the runway – no matter how spectacular – still made sense when broken down. When the garments were hanging on a rack, they still looked beautiful and worked for the customer.

How do you think fashion can continue exploring new codes of femininity without losing elegance?

When we talk about new codes of femininity, we’re entering very broad territory. Classic femininity may work for one person, but not for another. I actually think we shouldn’t be focusing on femininity or masculinity as fixed concepts anymore. If I show a piece on a female model, that shouldn’t stop a man from identifying with it or wanting to wear it. There shouldn’t be that disconnect between what we see and what we feel we can wear.

We need to open up that conversation and push those boundaries. In my case, both men and women come to wear my designs – and often, it’s the men who end up buying dresses. I don’t see a need to separate genders. And when we talk about femininity, I believe everyone interprets it in their own way, and all those interpretations are valid.

What do you hope the audience at 080 Barcelona Fashion takes away from your show?

I want people to walk away smiling. To see color, to feel joy. I want to leave them with a good vibe. We’re closing the second day of 080 Barcelona Fashion Week, and I want to be that final moment that leaves a sweet aftertaste. I want to bring happiness and share the idea that fashion can be fun. Because at the end of the day, that’s part of why we’re here too.

How do you see Spanish fashion today in the international context, and where does your brand fit into that landscape?

Spanish fashion is basically dead on the international stage. Outside our country, there’s little real knowledge of what’s being done here. There are designers working abroad—like Pablo Erroz or Arturo Obegero – and many of us are doing international work. But the problem is we’re not recognized as a group, and that’s the key.

A group of us started GenSpain, an initiative that, looking ahead, wants to change that. We know it’s hard to unify brand strategies, but our goal is to start doing joint actions that give us visibility as a collective. One of our ambitions is to organize an international show in Paris. We believe there’s a whole generation – not just of young designers – doing powerful work, and we need to unite in order to have a real impact beyond Spain.

Photography by Ángela Ibañez for VEIN MAGAZINE

Read more contents from 080 Barcelona Fashion

Follow us on TikTok @veinmagazine